My last post explained the thinking behind the softening of systems thinking – to include the reality of human beings into the mix.

My last post explained the thinking behind the softening of systems thinking – to include the reality of human beings into the mix.

I ended by noting that this naturally leads on to the hugely important question of how interventions into social systems (i.e. attempts at improving them) should be approached…

What’s the difference between…?

The word ‘Science’ is a big one! It breaks down into several major branches, which are often set out as the:

- Natural sciences – the study of natural phenomena;

- Formal sciences – the study of Mathematics and Logic; and

- Social sciences – the study of human behaviour, and social patterns.

Natural science can be further broken down into the familiar fields of the Physical sciences (Physics, Chemistry, Earth Science and Astronomy) and the Life sciences (a.k.a Biology).

The aim of scientists working in the natural science domain is to uncover and explain the rules that govern the Universe, and this is done by applying the scientific method (using experimentation1) to their research.

The key to any and every advancement in the Natural sciences is that an experiment that has supposedly added to our ‘body of knowledge’ (i.e. found out something new) must be:

- Repeatable – you could do it again (and again and again) and get the same result; and

- Reproduceable – someone else could carry out your method and arrive at the same findings.

This explains why all ‘good science’ must have been subjected to peer review – i.e. robust review by several independent and objective experts in the field in question.

“Erm, okay…thanks for the ‘lecture’…but so what?!”

Well, Social science is different. It involves humans and, as such, is complex.

The Natural science approach to learning (e.g. to set up a hypothesis and then test it experimentally) doesn’t transfer well to the immensely rich and varied reality of humanity.

“In [social science] research you accept the great difficulty of ‘scientific’ experimental work in human situations, since each human situation is not only unique, but changes through time and exhibits multiple conflicting worldviews.” (Checkland)

I’ll try to explain the enormity of this distinction between natural and social scientific learning with some examples, and these will necessarily return to those repeatability and reproducibility tests:

Unique: I’ll start with Chemistry. If you were to line up two beakers of water and (carefully) drop a small piece of sodium into each then you would observe the same explosive reaction…and, even though you could predict what would happen if you did it a third time, you’d still like to do it again 🙂

Unique: I’ll start with Chemistry. If you were to line up two beakers of water and (carefully) drop a small piece of sodium into each then you would observe the same explosive reaction…and, even though you could predict what would happen if you did it a third time, you’d still like to do it again 🙂

I was looking for a ‘social’ comparison and, following a comedy coffee conversation with a fellow Dad, the following observation arose: If you are a parent of two or more children, then you’ll know that consistency along the lines of ‘sodium into water’ is a pipe dream. I’ve got two teenage sons (currently 17 and 15 years old) and whenever I think I’ve learned something from bringing up the first one, it usually (and rather quickly) turns out to be mostly the opposite for the second! They are certainly unique.

The same goes for group dynamics – two different groups of people will act and react in different ways…which you won’t be able to fully determine up-front – it will emerge.

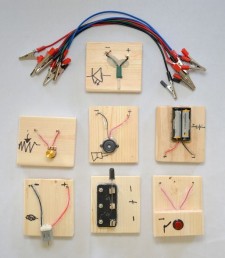

Changing over time: Now, over to Physics. If you were to select a battery, light bulb and resistor combination and then connect them together with cables in a defined pattern (e.g. in series) then you could work out (using good old Ohm’s law) what will happen within the circuit that you’ve just created. Then, you could take it all apart and put it away, safe in the knowledge that it would work in the same predictable way when you got it all out the next time.

Changing over time: Now, over to Physics. If you were to select a battery, light bulb and resistor combination and then connect them together with cables in a defined pattern (e.g. in series) then you could work out (using good old Ohm’s law) what will happen within the circuit that you’ve just created. Then, you could take it all apart and put it away, safe in the knowledge that it would work in the same predictable way when you got it all out the next time.

However, in our ‘social’ comparison, you can’t expect to do the same with people…because each time you (attempt to) do something to/with them, they change. They attain new interactions, experiences, knowledge and opinions. This means that it is far too simplistic to suggest that “we can always just undo it if we want to” when we are referring to social situations.

Just about every sci-fi movie recognises this fact and comes up with some ingenious device to ‘wipe people’s minds’ such that they conveniently forget what just happened to them – their memories are rewound to a defined point earlier in time. The ‘Men in Black’ use a wand with a bright red light on the end (hence their protective sunglasses…or is that also fashion?).

In reality, because such devices don’t exist (that I’m aware of), people in most organisations suffer from (what I refer to as) ‘Change fatigue’ – they’ve become wary of (what they’ve come to think of as) the current corporate ‘silver bullet’, and act accordingly. This understandably frustrates ‘management’ who often don’t want to see/ understand the fatigue2 and respond with speeches along the lines of “Now, just wipe the past from your mind – pretend none of it happened – and this time around, I want you to act like it’s really worth throwing yourself into 110%!”.

Mmmm, if only they could!

Conflicting worldviews: Finally, a Biology example. Let’s suppose that you’ve done a couple of lung dissections – one’s pink and spongy, the other is a black oogy mess3. Everyone agrees which one belonged to the 40-a-day-for-life smoker.

Conflicting worldviews: Finally, a Biology example. Let’s suppose that you’ve done a couple of lung dissections – one’s pink and spongy, the other is a black oogy mess3. Everyone agrees which one belonged to the 40-a-day-for-life smoker.

However, for our ‘social’ comparison, get a bunch of people into a room and ask them for their opinions on other people and their actions, and you will get wildly differing points of view – just ask a split jury!

The social phenomena of the ‘facts’ are subject to multiple, and changing, interpretations.

After reading the above you might be thinking…

“….so how on earth can we learn when people are involved?”

This is where I bring in the foundational work of the psychologist Kurt Lewin (1890 – 1947).

This is where I bring in the foundational work of the psychologist Kurt Lewin (1890 – 1947).

Lewin realised the important difference between natural and social science and came up with a prototype for social research, which he labelled as ‘Action research’.

“The method that [Lewin] evolved was of involving his subjects as active, inquiring participants in the conduct of social experiments about themselves.” (Argyris & Schon)

His reasoning was that:

“People are more likely to accept and act on research findings if they helped to design the research and participate in the gathering and analysis of data.” (Lewin & Grabbe)

Yep, as a fellow human being, I’d wholeheartedly agree with that!

Who’s doing the research?

I hope that you can see that the (potentially grand) title of ‘social research’ doesn’t presume a group of people in white lab coats attached to a University or such like. Rather, applied social research can (and should) be happening every minute of every day within your organisation – it does at Toyota!

Argyris and Schon wrote about two (divergent) methods of attempting to intervene in an organisation. They labelled these as:

- ‘Spectator – Manipulator’: a distant observer who keeps themselves at arms lengths from the worker, yet frequently disturbs the work with ‘experiments’ to manipulate the environment and observe the response;

and

- ‘Agent – Experient’: an actor who locates themselves within the problematic situation (with the people), to appreciate and be guided by it, to facilitate change (in actions and thinking) by better understanding of the situation.

You can see that the first fits well with natural science whilst the second fits with social.

‘The ‘spectator – manipulator’ method also describes rather well the reality of commanding and controlling, through attempting to implement (supposed) ‘best practise’ on people, and then rolling out ever wider.

The nice thing about action research is that the researcher (the agent) and the practitioner (the people doing the work) participate together, meaning that:

“The divide between practitioner and researcher is thus closed down. The two roles become one. All involved are co-workers, co-researchers and co-authors…of the output.” (Flood)

Proper4 action research dissolves the barrier between researcher and participant.

And, as such, ‘Action research’ is often re-labelled using the related term ‘Action learning’…. because that is exactly what the participants are doing.

A note on intervention

Any intervention into a social system causes change5. Further, the interventionist cannot be ‘separated from the system’ – they will change too!

Any intervention into a social system causes change5. Further, the interventionist cannot be ‘separated from the system’ – they will change too!

Argyris and Schon wrote that:

“An inquiry into an actor’s reasons for acting in a certain way is itself an intervention…[which] can and do have powerful effects on the ways in which both inquirer and informant construe the meaning of their interaction, interpret each other’s messages, act towards each other, and perceive each other’s actions. These effects can complicate and often subvert the inquirer’s quest for valid information.

Organisational inquiry is almost inevitably a political process…the attempt to uncover the causes of a systems failure is inevitably a perceived test of loyalty to one’s subgroup and an opportunity to allocate blame or credit…

[We thus focus on] the problem of creating conditions for collaborative inquiry in which people in organisations function as co-researchers rather than as merely subjects.”

You might think that taking a ‘spectator – manipulator’ approach (i.e. remaining distant) removes the problem of unintended consequences from intervening…but this would be the opposite. The more remote you keep yourself then the more concerned the workers will likely be about your motives and intentions….and the less open and expansive their assistance is likely to be.

So, as Argyris and Schon wrote, the best thing for meaningful learning to occur would be to create an appropriate environment – and that would mean gaining people’s trust….and we are back at action learning.

The stages of action research within an organisation

Action research might be described as having three stages6, which are repeated indefinitely. These are:

- Discovery;

- Measurable action; and

- Reflection

Discovery means to study your system, to find out what is really happening, and to drive down to root cause – from events, through patterns of behaviour, to the actual structure of the system (i.e. what fundamentally makes it operate as it does) …and at this point you are likely to be dealing with people’s beliefs.

…and to be crystal clear: the people doing the discovery are not some central corporate function or consultants ‘coming in’ – it’s the people (and perhaps a skilled facilitator) who are working in the system.

Measurable action means to use what you have discovered and, together, take some deliberate experimental action that you (through consensus) believe will move you towards your purpose.

But we aren’t talking about conventional measurement. We’re referring to ‘the right measures, measured right’!

Reflection means to consider what happened, looking from all points of view, and consider the learning within…. leading on to the next loop – starting again with discovery.

This requires an environment that ensures that open and honest reflection will occur. That’s an easy sentence to write, but a much harder thing to achieve – it requires the dismantling of many conventional management instruments. I’m not going to list them – you would need to find them for yourselves…which will only happen once you start your discovery journey.

What it isn’t

Action research isn’t ‘a project’; something to be implemented; best practise; something to be ‘standardised’…(carry on with a list of conventional thinking).

If you want individuals, and the organisation itself, to meaningfully learn then ‘commanding and controlling’ won’t deliver what you desire.

…and finally: A big caveat

Peter Checkland adopted action research as the method within his Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) and yet he was highly critical of “the now extensive and rapidly growing literature” on the approach, calling it “poverty stricken”. Here’s why:

Peter Checkland adopted action research as the method within his Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) and yet he was highly critical of “the now extensive and rapidly growing literature” on the approach, calling it “poverty stricken”. Here’s why:

“The great issue with action research is obvious: what is its truth criterion? It cannot be the repeatability of natural science, for no human (social) situation ever exactly duplicates another such situation.” (Checkland)

The risk of simply saying “we’re doing action research” is that any account of what you achieved becomes nothing more than plausible story telling. Whilst social research can never be as solid as the repeatable and reproduceable natural science equivalent, there must be an ‘is it reasonable?’ test on the outcomes for it to be meaningful.

There’s already plenty of ‘narrative fallacy’ story telling done within organisations – where virtually every outcome is explained away in a “didn’t we do well” style.

To be able to judge outcomes from action research, Checkland argues that an advanced declaration is required of “what constitutes knowledge about the situation. This helps to draw the distinction between research and novel writing.”

This makes the action research recoverable by anyone interested in subjecting the work to critical scrutiny.

So what does that mean? Well, taking John Seddon’s Vanguard Method7 as an example, the Check stage specifically starts up front with:

- Defining the purpose of the system (from the customer’s perspective – ‘outside in’);

- Understanding the demands being placed on the system (and so appreciating value from a wide variety of customer points of view); and

- Setting out a set of capability measures that would objectively determine whether any subsequent interventions have moved the system towards its purpose.

…and (in meeting Checkland’s point) this is done BEFORE anyone runs off to map any processes etc.

In summary:

We need to appreciate “the role of surprise as a stimulus to new ways of thinking and acting.” (Argyris & Schon).

People should be discovering, doing and seeing for themselves, which will create a learning system.

Footnotes:

1. Experiments: If you’d like a clearer understanding of experiments, and some comment on their validity then I wrote about this in a very early post called Shonky Experiments

2. Not wanting to see the change fatigue: This would happen if a manager is feverishly working towards a ‘SMART’ KPI, where this would be exacerbated if there is a bonus attached.

3. Lung dissection: I was searching around for an image of a healthy and then a smoker’s lungs…but thought that not everyone would like to see it for real…so I’ve put up an image with a collection of surgical scalpels – you can imagine for yourself 🙂

4. Proper: see the ‘big caveat’ at the end of the post.

5. Such changes may or may not be intended, and may be considered as positive, negative or benign.

6. Three stages of action research: If I look at the likes of Toyota’s Improvement/Coaching Katas or John Seddon’s Vanguard Method then these three stages can be seen as existing within.

7. The Vanguard Method is based on the foundation of action research.

Another timely post! I’m ‘leading’ an intervention at the moment and I’ve got ‘relatively’ free rein for once so it’s as close to Vanguards ‘check’ that I’ve ever been able to help with.

We’re using visual logs of each change, logging issues, suggesting countermeasures and seeing the impact.

The biggest challenge is trust and change fatigue. It is a Command and Control organisation which I am facilitating unlearning.

I took quite a lot of pride this morning quietly observing previously passive people becoming ‘Agent- Experimenter’.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Sounds good! Thanks for sharing 🙂

LikeLike

Agree with every word of that.

I work as an internal interventionist. To date, I’ve generally been successful at creating the open and honest environment for action learning. Teams I’ve facilitated have had amazing normative learning experiences, and as this post suggests will happen, so have I.

The problem I experience is that the better the environment you create, the more the team’s mental models shift. Obviously that’s good, but it puts distance between them and their colleagues at the coalface while Check and Redesign are taking place.

I’ve tried various ways to engage the wider workforce, but invariably there is a level of suspicion of the team. The usual tropes – brainwashing, cults, etc. That eventually unwinds (or not) during Roll-in, but I’d be interested in any tactics you’ve tried for mitigating this effect while maintaining the quality of the learning experienced by the intervention team.

LikeLike

Thanks for adding a comment….and here’s some random thoughts:

Obviously I can’t know the work you have been doing and how you have been doing it. However, I’d comment that I’m aware of instances where intervention teams have been carved out of (i.e. separated from) the workforce to ‘do’ action learning – they go on to have an amazing experience and then have huge trouble when it comes to ‘getting them’ (i.e. those who weren’t in the so-called intervention team) to change. No surprises really.

I think real care needs to be taken to ensure that a whole value stream (or process within) comes on the journey together. You might think this would be too slow but it’s a case of ‘go slow to go fast’.

Sure, not everyone can (or should) be doing everything, but they need to become aware of the philosophy (which will come over time) and to be included throughout any method. Anyone that feels ‘left out’ will likely be in personal protection mode;

I’d recommend studying Toyota (not as in manufacturing but as in how they create a people system), particularly the work of Mike Rother and Jeffrey Liker.

The right underlying philosophy is more important than method. The former should stay constant whilst the latter can change as you (all) learn. It’s the philosophy that you want the wider people to see and become interested in, rather than creating a ‘them and us’ battle between different methods;

If the problem is that your successful work within sub-systems is butting up against the larger organisational system…then this is a far bigger challenge (and will depend upon things like the ownership structure and senior management’s beliefs and behaviours as to whether structural issues are preventing change);

The best way to make the bigger system curious would be to have real (meaningful and sustained) success in a sub-system that, frankly, amazes (and therefore confuses) them…such that they want to know what was done;

A big (and regular) mistake that people can make is to achieve wonderful action learning within an area and (almost without realising it) attempt to push this onto others (in words and even deeds)….you can’t learn for other people – everyone has to go through their journey, and this will only happen if they want to…which comes back to curiosity;

You can work on curiosity in others by drip feeding them with stuff…not too small that they think they ‘already know it’ and not too big that it scares or deeply challenges them. This is actually why I started this blog back in 2014 – to get people reading, thinking, sharing and talking about the underlying philosophy that enables purpose-seeking organisations.

…I’m not sure if any of that helps. I don’t have a silver bullet, though there’s plenty of advice within my historic posts (ref. ‘Crossing the Divide’, ‘Rolling, rolling, rolling’, ‘Depths of Transformation’ and so on).

Perhaps you could work with all those that, through your work, now ‘get it’ and perform discovery with them on what they’ve experienced in working with others. Perhaps there are some experiments to try? And then some reflections to be had.

Cheers,

Steve

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers Steve.

I think you’ve nailed it and it’s a bit of both the problems you note. We (loosely) follow the Vanguard Method, which tends to involve intervention teams being ‘carved out’ as you describe. It’s fine up to a point, but there’s definitely an issue with scale if you have an intervention team of half a dozen trying to drive change in a large service area and it can create precisely the ‘personal protection mode’ that you refer to, particularly among managers.

We’ve been thinking more recently about working in small sub-systems with the entire team, starting with the leadership, and our first attempts with that have been promising,

More generally – yes – we have successful work in many sub-systems that is sub-optimised by the wider organisational design and thinking. This creates dissonance on an almost daily basis that can sometimes be unpleasant. But… we are generating curiosity in a positive way in many places by simply sharing our experiences with any willing audience and demonstrating sustained improvement in a (hopefully) not boastful way. We do get more genuine ‘pulls’ from unexpected places than we used to, so I remain optimistic.

Thanks for your thoughts anyway – really helpful.

LikeLiked by 1 person