This post is a long, meaty one. So, if this interests you, make yourself a cup of tea and settle in. If it’s not for you, no worries, ‘as you were’…but still make yourself that cuppa 🙂

This post is a long, meaty one. So, if this interests you, make yourself a cup of tea and settle in. If it’s not for you, no worries, ‘as you were’…but still make yourself that cuppa 🙂

I first ‘got into’ systemsy stuff about 20 years ago1. I began with W. Edwards Deming (a peripheral figure in the systems literature) and then went in a variety of directions.

These include:

- A number of ‘systems theorists’, such as Forrester, Meadows, Beer, Ackoff & Checkland

- John Seddon’s work (noting his down-to-earth writings2)

- Dave Snowden’s work (noting his desire for precision3)

As an aside: I’m a big fan of Mike Jackson’s work4 to clearly lay out ‘who’s thought what’ in the systems space, and his aim of providing a balanced ‘value vs. critique’ review on each.

During my journey – and most recently via the wonders (or is that curse?) of social media – I’ve noted what I might describe as various ‘turf wars’ going on. If you’ve been following along (e.g. Twitter, LinkedIn,…) then you could be forgiven for believing that the three groups noted above (or at least their thinking) are ‘poles apart’.

I’d agree that it’s very healthy for people to robustly test their thinking against others5 – it’s incredibly useful to understand a) boundaries of application and b) where there is more work to be done.

However, I feel that those trying to follow along could end up ‘throwing the baby out with the bathwater’ because we fail to see (or acknowledge) the significant intersections between the groups.

This post is about me exploring (some of) what I see as useful intersections.

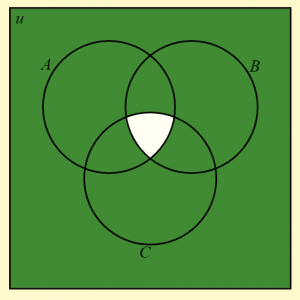

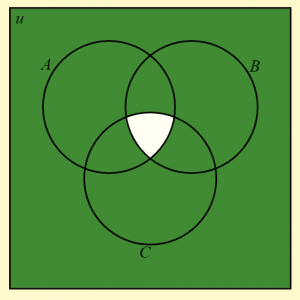

I love a diagram, so I’ll use the one below to anchor what follows. It’s the typical Venn diagram, highlighting three sets and the relationships between them. The overlaps are the intersections:

I’m mainly concerned with the ‘Snowden – Seddon’ intersection within this post (because this currently interests me the most). You’ll have to bear with me on this because the intersections may not be apparent to those reading their work or listening to them speak. Further, they themselves may not accept my (current) view about if, and how, they intersect.

As an aside: I’d note that it’s not uncommon for similar things to be discovered/ worked out by different people in different settings…and this (almost inevitably) means that they will talk about similar things but use different language (or notation) to each other.

A couple of celebrated examples that I’m aware of:

- Newton and Leibniz re. the invention of calculus

- Darwin and Wallace re. the theory of evolution

The trick (so to speak) would be to spot the intersections and then build upon them. Newton and Leibniz (and their supporters) had an argument. Darwin and Wallace entered a collaboration.

I’ve thought about the following ‘Snowden – Seddon’ intersections:

- On making sense of the problem space

- On working with complexity

- On the importance of failure

- On facilitating change within the complex domain

- On scaling change within the complex domain

- On measurement

- Combining quantitative with qualitative

- On the use of tools

- On systems theory

Each explanation below will have two halves. I’ll start with a Snowden perspective, and then move to a Seddon viewpoint. Each half will deliberately begin with “as I understand it” (I’ll underline these so that you can clearly see me swapping over).

Here goes…

1. On making sense of the problem space

As I understand it, Snowden’s Cynefin framework6 aims to help decision makers make sense of their problem space…so that they respond appropriately. It very usefully differentiates (amongst many other things) between ordered and complex domains. In short:

As I understand it, Snowden’s Cynefin framework6 aims to help decision makers make sense of their problem space…so that they respond appropriately. It very usefully differentiates (amongst many other things) between ordered and complex domains. In short:

- An ordered system is predictable. There are known, or knowable cause-and-effect relationships and, because of this, there are right answers;

- A complex system is unpredictable. The elements (for example people) influence and evolve with one another. The past makes sense in retrospect (i.e. it is explainable) BUT this doesn’t lead to foresight because the system, and its environment, are constantly changing. It’s not about having answers, it’s about what emerges from changing circumstances and how to respond.

As I understand it, Seddon realised that there is a seriously important difference between a manufacturing domain and a service domain and that this difference had huge implications as to how decision makers should act.

- A widget being manufactured requires a level of consistency. Further, it is an inanimate object (ref: I’m just a spanner!);

- A human being needing help from a service is unique. Further, they have (a degree of) agency;

- As such, any system design needs to properly take this into account. An ordered response (e.g. pushing standardised ‘solutions’) to a complex problem space will not work out well (ref. failure demand7).

Of interest to me is that, whilst the widget production line may fit the ordered problem space, it usually involves human beings to run it. So, at a 2nd order level, it is complex – those workers are unique and possess agency. It would be a good idea to design a system that engaged their brains and not just their motor skills.

From reading about the Toyota Production System (TPS) over the years, I believe that this is perhaps what Taiichi Ohno and his colleagues knew… and what those merely trying to copy them didn’t (ref: Depths of ‘Transformation’).

As I understand it, Seddon would suggest that there are a number of service archetypes8 (from transactional…through to people-centred). I see people-centred as being the closest intersection with Snowden’s complex problem space, which leads on to…

2. On working with complexity

As I understand it, Snowden would suggest that the appropriate way to work with complexity would be to:

As I understand it, Snowden would suggest that the appropriate way to work with complexity would be to:

- encourage interactions

- experiment with possible ways forward

- monitor what emerges and adjust accordingly

- be patient: allow time for outcomes to emerge, and for reflection

I understand that this may be summarised as probe – sense – respond.

As I understand it, Seddon would suggest that the appropriate way for people-centred services to work would be to:

- provide ‘person – helper’ continuity, to build trusting relationships between them

- take the time to understand the person, their situation, and their needs

- provide ‘person – helper’ autonomy: to try things, to reflect, to adjust according, to go in useful directions according to what emerges

I understand that this may be summarised as designing a system that can absorb variety rather than trying to specify and control.

I see a very strong intersection between the two. I see Seddon as arguing against an ordered response within a people-centred domain.

I note that Snowden uses the metaphor of the resilient salt marsh as compared to the robust sea wall. The former can absorb the variety of what each ‘coming of the tide’ presents, whilst the latter predictably responds but can’t cope when its utility is breached. Seddon is arguing for a ‘salt marsh’ people-centred system design, rather than the conventional sea wall.

3. On the importance of failure

As I understand it, Snowden is clear that we humans learn the most from failure – because we are exposed to the unexpected, and have to wrestle with the consequences (ref. reflection).

As I understand it, Snowden is clear that we humans learn the most from failure – because we are exposed to the unexpected, and have to wrestle with the consequences (ref. reflection).

We may learn little from supposed ‘success’, where everything turns out as expected. We risk complacency.

As I understand it, Seddon arrived at the definition of failure demand7 because he realised that:

- those accountable for the performance of a system are often (usually) not aware of the types (and frequencies) of failure demands caused by its current design

- the act of seeing, and pondering, failure demand exposes them to reality, and provides a powerful lever for reflection as to why it occurs…and to new ways of thinking about design.

I would link the idea of ‘inattentive blindness’ (as regularly explained by Snowden) – where we may not see what is in plain sight (ref. the case of the radiologists and a gorilla).

Seddon’s method of uncovering failure demand is to enable management to begin the journey of seeing their gorilla(s).

4. On facilitating change within the complex domain

As I understand it, Snowden and his colleagues have defined a set of principles to follow, a key tenet of which is to design the change process in such a way that participants ‘see the system’ and discover insights for themselves (as opposed to being given answers).

As I understand it, Snowden and his colleagues have defined a set of principles to follow, a key tenet of which is to design the change process in such a way that participants ‘see the system’ and discover insights for themselves (as opposed to being given answers).

As such, the role of the facilitator [interventionist] is to provide an environment in which the participants’ learnings can emerge. Those facilitating do not (and should not) act as ‘experts’. Further, the responsibility for producing an outcome shifts from facilitator to the group of participants.

As I understand it, Seddon’s life work centres around intervention theory and that ‘true human change is normative’ – people changing their thinking, where this is achieved through experiential learning. This would be the opposite of rational attempts at change via ‘you talk, they listen’.

As such, the role of the interventionist is to provide a method whereby they act as a ‘mirror, not an expert’ (ref. ‘Smoke and mirrors’). Further, the responsibility for outcomes lays squarely with those who are accountable for the system in question (ref. ‘leader-led’). ‘Change’ cannot be outsourced to the interventionist9.

5. On scaling change within the complex domain

Given the intersection above, it follows that it matters how we go about scaling change.

Given the intersection above, it follows that it matters how we go about scaling change.

As I understand it, Snowden lays out the principle that:

“you don’t scale a complex system by aggregation and imitation. You scale it by decomposition and recombination.”

This area of thinking is currently a stub within the Cynefin wiki, which suggests that it is yet to be clearly set out. However, (to me) it is stating that you can’t just ‘copy and paste’ what apparently worked with one group of humans onto another. Well, you could try…. but you can expect some highly undesirable outcomes if you do (ref. disengagement, disenfranchisement, defiance…)

It also says to me that you can expect different ‘solutions’ to come from different groups, and this is completely fine if they are each ‘going in a useful direction’. Further, they can then learn from each other (ref. parallel experiments and cross pollination of ideas).

As I understand it, Seddon makes clear the problem with ‘rolling out’ (attempting to implement) change onto people. Instead, he defined the concept of ‘roll in’:

“Roll in: a method to scale up change to the whole organisation that was successful in one unit. Change is not imposed. Instead, each area needs to learn how to do the analysis for themselves and devise their own solutions. This approach engages the workforce and produces better, more sustainable results.”

It’s not about finding an answer, it’s about moving to a new way of working whereby it is the norm for those in the work to be experimenting, collaborating, learning, and constantly moving to better places (ref. Rolling, rolling, rolling)

6. On measurement

As I understand it, Snowden holds that the appropriate way to measure change within a complex system is with a vector – i.e. speed and direction, from where we were to where we are now. This is instead of acting in an ordered way of setting a goal and defining actions to achieve it (which incorrectly presumes predictability).

As I understand it, Snowden holds that the appropriate way to measure change within a complex system is with a vector – i.e. speed and direction, from where we were to where we are now. This is instead of acting in an ordered way of setting a goal and defining actions to achieve it (which incorrectly presumes predictability).

As I understand it, Seddon’s colleague, the late Richard Davis, set out measurement of people-centred help in a similar ‘speed and direction’ manner (ref. On Vector Measurement for a more detailed discussion).

“But what about ‘Purpose’?”: You may know that Seddon is laser-focused on the purpose of a service system, from the point of view of those that it is there to help (e.g. the customer). This purpose acts as an anchor for everyone involved.

You might think that Seddon’s ‘purpose’ view clashes with Snowden’s ‘don’t set a goal within a complex system’ view.

I don’t see ‘purpose’ (as Seddon uses it) to be the setting of an (ordered) goal. I see it more as setting out the desirable emergent property if the system in question was ‘working’.

I probably need to set that out a bit more clearly. Here goes my attempt:

Definition: Emergent system behaviours are a consequence of the interactions between the parts.

Example: The individual parts of a bird (its bones, muscles, feather etc) do not have the ability to overcome gravity. However, when these parts usefully inter-relate, they create the emergent property of ‘flight’…and yet ‘flight’ is not a part that we can point at. It is something ‘extra/ more than’ the parts.

…and so to Purpose: The definition of the desirable emergent property (i.e. what we would ideally want ‘the system’ to be achieving) allows a directional focus. It’s not an ordered goal, with a set of specified actions to achieve. It’s a constant sense-check against “are we (metaphorically) flying?”

In a people-centred service, it would be “are we actually helping people [with whatever their needs are]?”

7. Combining quantitative with qualitative

As I understand it, Snowden would say that there is a need to combine stories and measurement.

As I understand it, Snowden would say that there is a need to combine stories and measurement.

“Numbers are objective but not persuasive. Stories are persuasive but not objective. Put them together.” (Captured from Snowden workshop Aug. ‘22)

The power in stories is that they are authentic – they possess many useful qualities such as:

- an actuality (evidence rather than opinion)

- showing variation (noting that ‘the average’ doesn’t exist)

- revealing ambiguity (causing us to think deeply about)

- …etc.

However, given this, those wanting to understand at a ‘system level’ need to combine the micro into a macro picture – to see the patterns within (ref. Vector Measurement as per above).

As I understand it, Seddon tells us to study ‘in the work’ (get knowledge) and that this can be done by observing demands placed on the system in focus, and in following the flow of those demands – from need through to (hopefully) its satisfaction, and everything that happens (or doesn’t) in-between.

A case study can be a powerful story, providing an authentic understanding (from the customer’s point of view) of:

- why this particular scenario arose

- what happened10 and the associated ‘lived experience’, and

- (with the appropriate reflection) why it occurred in this manner (ref. system conditions)

However, whilst such case studies can be eye-opening, they may be dismissed as ‘not representative’ if used on their own – the risk of ‘just dealing in anecdotal stories’.

They need to be combined with macro measures that show the predictability of what the stories evidence (ref. demand types and frequencies, measures of flow,…[measures against that desirable emergent purpose])

In short, the micro and the macro are complimentary. Both are likely to be necessary.

8. On the use of tools

As I understand it, Snowden and his collaborators are clear that there may be ‘lots of tools out there’ but its very important to ‘know enough’ before applying a tool (ref: ‘bounded applicability’):

As I understand it, Snowden and his collaborators are clear that there may be ‘lots of tools out there’ but its very important to ‘know enough’ before applying a tool (ref: ‘bounded applicability’):

“If we work with tools without context, in other words we don’t know enough to know the tool doesn’t fit the situation, the intervention will suffer, as will the overall outcome.” (Viv Read, Cynefin: weaving sense-making into the fabric of our world)

As I understand it, Seddon sets out the dangers of attempting to produce change via merely applying tools (ref. Seddon’s ‘Watch out for the Toolheads’ admonition) and the risk of using the wrong ‘tool’ on the wrong problems:

“The danger with codifying method as tools is that, by ignoring the all-important context, it obviates the first requirement to understand the problem” (Seddon)

I believe that Snowden and Seddon would concur that the start is to understand the problem space, and then (and only then) pick up, or design, applicable tools to assist. Conversely, I believe that they would rebuke anyone carrying around a codified method (‘tool’), looking for any place to use it.

9. On ‘Systems Theory’

As I understand it, both Snowden and Seddon are critical of aspects of systems theory.

- Snowden argues against the (so called) hard forms of systems theory (ref. Cybernetics, System Dynamics)

- Seddon argues for a practical approach that starts with studying ‘in the work’, to get knowledge.

Whilst their critiques may differ, the fact that they think differently to others re. systems theory is an intersect 🙂

I think that they would align with the following quote:

“[Theory] without [method] is a daydream. [Method] without [theory] is a nightmare”

“What a load of rubbish!”

To those ‘Seddonistas’11 or ‘Snowdenites’ out there who may baulk at the intersections above, I’m not suggesting that John Seddon and Dave Snowden think the same. I’m also not suggesting any superiority (of ideas) between them. Far from it. I believe that they’ve been on very different journeys (haven’t we all?).

“So, it’s nirvana then?”

Nope – I’m not proposing that I’ve solved anything/ moved things to new places. I just find (what I see as) intersections to be interesting and potentially useful to ponder/work with/ build on.

I don’t expect that Snowden and Seddon are fully aligned – I’m (almost) sure that there’s plenty in the Venn diagram that doesn’t overlap.

As an aside, I think that Snowden and Seddon have both developed a reputation for ‘saying what they think’. I really like their desire, and ability, to provide solid critique – that ‘cuts through the crap’.

I do hope, though, that those geniuses amongst us ninnies (e.g. Snowden, Seddon) focus on education, rather than guru status.

Further work: On the other intersections

I expect that there are lots of ‘thinking things’ that fit into the other intersections:

- Where Snowden overlaps with the systems theorists

- Where Seddon overlaps with the systems theorists

- Where all three overlap

You may also be able to point to yet more ‘Snowden – Seddon’ intersections.

You are welcome to take this on as ‘homework’ 🙂

Addendum: Please see this link to an addendum referring to a response from Dave Snowden.

Footnotes

1. I’m not claiming expertise. I am but an amateur with a great deal more to learn.

2. An enjoyable read: John has written a number of books to date. I’ve found them a joy to read. This contrasts with other books, which can be torture.

3. Precision and words: If you know of Snowden’s work, you’ll probably be aware that it’s littered with (what I see as) ‘new words’, or at least new uses for them.

4. Mike Jackson’s book is called ‘Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity’.

5. Robust testing: personally, I’d like such testing to be carried out in a highly respectful (mana enhancing) way.

6. The Cynefin framework is set out (amongst other places) in Snowden and Boone’s ‘A Leader’s framework for decision making’, HBR Nov. 2007.

7. Failure demand was defined by Seddon as “Demand caused by a failure to do something, or to do something right for the customer”. It might also be called/ thought of as ‘preventable demand’. Its opposite is Value demand.

8. Service archetypes: See ‘Autonomy – autonomy support – autonomy enabling’ for an explanation from my perspective.

9. Attempts at outsourcing change: This is why all those outsourced improvement projects, carried out by specialist improvement roles don’t result in transformational change (ref. all those typical Lean Six Sigma ‘Green belt’ projects etc.).

10. What happened: the scope of a case study could range from a journey:

-

- over a couple of days (likely relevant to a transactional archetype)

- over weeks/ months (likely relevant to a process archetype)

- to many years (a people-centred archetype)

11. ‘Seddonistas’ is a playful term I read in Mike Jackson’s book (ref. the chapter on the Vanguard Method). It refers to those that passionately ‘support’ John Seddon. I’ve made up the ‘Snowdenites’ word to provide a pairing (I think it’s fair to do so as I believe that I have noted a similar ‘supporters club’ phenomenon for Dave Snowden).

12. Image credits: Climber scaling cliff image by ‘studio4rt on Freepik’

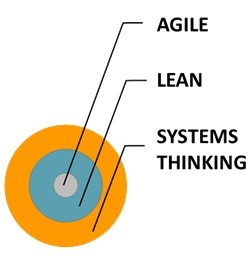

I feel like the phrase ‘Systems Thinking’ is, unfortunately, regularly abused/ misused/ confused and I wanted to write a post that causes me to set this out.

I feel like the phrase ‘Systems Thinking’ is, unfortunately, regularly abused/ misused/ confused and I wanted to write a post that causes me to set this out.

So I heard a really good question at a meeting recently, which (with a touch of poetic licence) I’ll set out as follows:

So I heard a really good question at a meeting recently, which (with a touch of poetic licence) I’ll set out as follows: Agile:

Agile:

System Thinking:

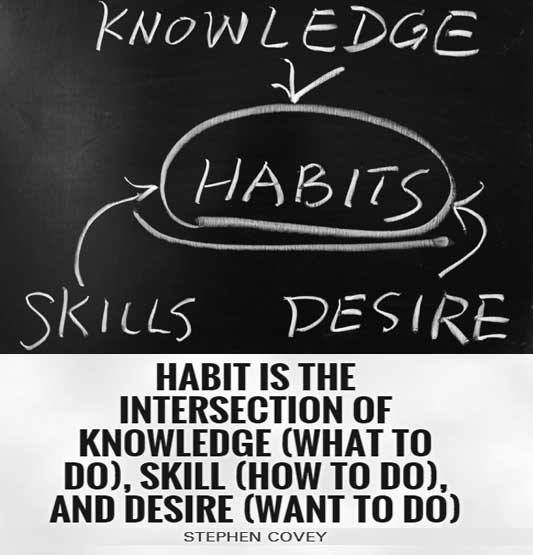

System Thinking: What habits need to be learned and practised to enable ‘Systems Thinking’?

What habits need to be learned and practised to enable ‘Systems Thinking’? If I absolutely had to link them together then I quite like this diagram because:

If I absolutely had to link them together then I quite like this diagram because: This post is about something that I find very interesting – Systems Thinking as applied to organisations, and society – and about whether there are two different ‘factions’….or not.

This post is about something that I find very interesting – Systems Thinking as applied to organisations, and society – and about whether there are two different ‘factions’….or not. He went on to develop ‘Open Systems theory’, which considers an organism’s co-existence with its environment.

He went on to develop ‘Open Systems theory’, which considers an organism’s co-existence with its environment. The study of systems really got moving from the 1940s onwards, with many offshoot disciplines.

The study of systems really got moving from the 1940s onwards, with many offshoot disciplines.

So where did that ‘hard’ term come from and why?

So where did that ‘hard’ term come from and why? This ‘worldview’ concept is easily understood, and yet incredibly powerful. At its most extreme, it deals efficiently with the often-cited phrase that ‘one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter’.

This ‘worldview’ concept is easily understood, and yet incredibly powerful. At its most extreme, it deals efficiently with the often-cited phrase that ‘one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter’. “Management thinking affects business performance just as an engine affects the performance of an aircraft. Internal combustion and jet propulsion are two technologies for converting fuel into power to drive an aircraft.

“Management thinking affects business performance just as an engine affects the performance of an aircraft. Internal combustion and jet propulsion are two technologies for converting fuel into power to drive an aircraft.  You will tell your manager what you think he/she wants to hear, and provide

You will tell your manager what you think he/she wants to hear, and provide  Governments all over the world want to get the most out of the money they spend on public services – for the benefit of the citizens requiring the services, and the taxpayers footing the bill.

Governments all over the world want to get the most out of the money they spend on public services – for the benefit of the citizens requiring the services, and the taxpayers footing the bill. He takes us through a case study of a real person in need, and their interactions with multiple organisations (many ‘front doors’) and how the traditional way of thinking seriously fails them and, as an aside, costs the full system a fortune.

He takes us through a case study of a real person in need, and their interactions with multiple organisations (many ‘front doors’) and how the traditional way of thinking seriously fails them and, as an aside, costs the full system a fortune. He identifies three survival principles in play, and the resulting anti-systemic controls that result:

He identifies three survival principles in play, and the resulting anti-systemic controls that result: Cox makes the obvious point that the actual redesign can’t be explained up-front because, well…how can it be -you haven’t studied your system yet!

Cox makes the obvious point that the actual redesign can’t be explained up-front because, well…how can it be -you haven’t studied your system yet! [Once you’ve successfully redesigned the system] “The primary focus is on having really good citizen-focused measure: ’are you improving’, ‘are you getting better’, ‘is the demand that you’re placing reducing over time’.”

[Once you’ve successfully redesigned the system] “The primary focus is on having really good citizen-focused measure: ’are you improving’, ‘are you getting better’, ‘is the demand that you’re placing reducing over time’.” My recent serialised post titled

My recent serialised post titled  A positive example of this phenomenon: The All Blacks won the rugby World Cup in 2011 and 2015, making them the first team ever to achieve ‘back-to-back’ rugby World Cups. They did this with a core of extremely influential world-class players3…who then promptly retired!

A positive example of this phenomenon: The All Blacks won the rugby World Cup in 2011 and 2015, making them the first team ever to achieve ‘back-to-back’ rugby World Cups. They did this with a core of extremely influential world-class players3…who then promptly retired! So, staying with rugby, let’s move to the English national team. In contrast to the All Blacks, they have had two terrible World Cups.

So, staying with rugby, let’s move to the English national team. In contrast to the All Blacks, they have had two terrible World Cups.

I’m a big fan of the Think Purpose blog. It gives me a good hearty laugh, and long may it continue.

I’m a big fan of the Think Purpose blog. It gives me a good hearty laugh, and long may it continue. Warning (or advert for some): Sometimes I write long(er) ‘foundational’ type posts – this is one of them 🙂

Warning (or advert for some): Sometimes I write long(er) ‘foundational’ type posts – this is one of them 🙂 A deterministic system is one which has no purpose and neither do its component parts. This might seem rather strange…”Erm, I thought you said a system had to have an aim?!” – the point is that a deterministic system normally serves a purpose of an entity external to it, such as its creator. Its function, and that of its parts, is simply to provide that service when required.

A deterministic system is one which has no purpose and neither do its component parts. This might seem rather strange…”Erm, I thought you said a system had to have an aim?!” – the point is that a deterministic system normally serves a purpose of an entity external to it, such as its creator. Its function, and that of its parts, is simply to provide that service when required. An animated system is one which does have a purpose of its own but its parts don’t.

An animated system is one which does have a purpose of its own but its parts don’t. A social system is one which has a purpose of its own and so do its parts (the people within).

A social system is one which has a purpose of its own and so do its parts (the people within). I’d suggest that every day in our working (and home) lives we are asked for our opinion on something. In fact, such a situation probably occurs dozens of times every single day.

I’d suggest that every day in our working (and home) lives we are asked for our opinion on something. In fact, such a situation probably occurs dozens of times every single day.