This post discusses a ‘how’ and follows on from a discussion of the ‘what and why’ in Part 1: Autonomy – Autonomy Support – Autonomy Enabling (a Dec ’21 post – it only took me 7 months!)

This post discusses a ‘how’ and follows on from a discussion of the ‘what and why’ in Part 1: Autonomy – Autonomy Support – Autonomy Enabling (a Dec ’21 post – it only took me 7 months!)

I’ll assume you know that the ‘how’ I am writing about is with respect to an approach to moving a large people-centred system:

- from (attempted) control

- to autonomy (and its enablement).

Please (re)read ‘part 1’ if you need to (including what is meant by people-centred)

Oh for the luxury of a ‘Green field’!

You could be fortunate to start in a relatively ‘green field’ situation (i.e. with very little already in place).

This is what Jos de Blok did in 2006 when he founded the community healthcare provider Buurtzorg in the Netherlands. He started with a few like-minded colleagues to form a self-managed team (i.e. an autonomous unit), and when it reached a defined size (which, in their model, is a team of 12), it ‘calved off’ another autonomous unit.

Buurtzorg carried on doing this until, 10 years later, there were 850 highly effective self-managing teams (autonomous units) in towns and villages all over the country.

In doing this, the autonomous units evolved the desire to have some (very limited) support functions, that would enable (and most definitely not attempt to control) them.

Sounds wonderful.

But many (most) of us don’t have this green field scenario.

We are starting with huge organisations, with thousands of workers within an existing set of highly defined (and usually inflexible) structures. The local, regional and (usually large and deeply functionalised) central model exist in the ‘here and now’.

So, the Buurtzoorg example (whilst recognised as a brilliant social system) is limited.

Rather, we would do well to look to an organisation that successfully changed itself after it had become a big control system. And Handelsbanken is, for me, a highly valuable organisation to study in this regard.

Some context on Handelsbanken

I recall writing about Handelsbanken and their forward-thinking CEO Jan Wallander some time back…and, after searching around, found a couple of articles that I wrote five years ago (how time flies!). A reminder if you are interested:

I’ve added some historical context1 in a footnote at the bottom of this post, but the upshot is that the results have been hugely impressive, such that they have been written into management case studies and books. Wallander successfully transformed the organisation, for the long term. It is now an International bank (across 6 countries) and turned 150 years old in 2021. It continually wins awards for customer satisfaction, financial safety, and sustainability.

I should deal with a likely critique before I go any further:

“But it’s a bank Steve!!!” Over the last few years, my area of interest has become the social sector (rather than ‘for profit’ organisations)…and, if you’ve noticed this, you may be questioning my use of a bank for this ‘Part 2’ post.

I’d respond that much of Jan Wallander’s thinking fits incredibly well for organisational design within the social sector. He saw that the answer was ‘about the long-term client journey’ (people-centred), within a community and NOT about pushing ‘products and services’.

An introduction to the ‘how’

I’ll break up my explanation into:

- Some key ‘up-front’ points;

- How Wallander achieved the transformation; and

- The core of Wallander’s organisational design

Some key ‘up front’ points

“As a rule, it is large and complex systems and structures that have to be changed if a real change is to take place.” [Wallander]

- There is no magic ‘let’s do another change programme’ silver bullet. It is a change in organisational paradigm

- It will take time and, above all, leadership (in the true meaning of the word)

- Most important for the ‘leadership’ bit is that those leading ‘get the why’. Constancy of purpose can only come from this

How Wallander achieved the transformation

Saying and doing are quite different things. I expect that I could have lots of agreeable conversations with people throughout an organisation (and particularly with those at its ‘centre’) about ‘autonomy at the front line, with enablement from the centre’…and yet nothing would change.

Saying and doing are quite different things. I expect that I could have lots of agreeable conversations with people throughout an organisation (and particularly with those at its ‘centre’) about ‘autonomy at the front line, with enablement from the centre’…and yet nothing would change.

The following quote interests me greatly:

“The reason why [such an ‘autonomy and enabling’ system] is so rare and so difficult to achieve is quite simply that people who have power…are unwilling to hand part of it over to anyone else – a very human reaction. So, if one is to succeed, one needs a firm and clear goal and one has to begin at the top…with oneself.” [Wallander]

Which leads on to…

Wallander’s head office problem

“The staff working at the head office saw themselves as smarter, better educated and ‘more up-to-date’ than the great mass of practical men and women out in the field. They also felt superior because they were in close contact with the highest authority [i.e. the members of the senior management team].

A steady stream of instructions…poured out from the head office departments…amounting to several hundred a month. Even if a branch manager was critical of these instructions and recommendations, he did not feel he had any possibility of questioning them.” [Wallander]

Wallander saw things very differently to this:

“The new policy…aimed at turning the pyramid upside down and making the branch office2 the primary units.

In the old organisation there was a clear hierarchy: at the bottom of the scale were the branch offices, and on the next step up the [regional] centres. [‘Success’ was] a move up to a post at the head office.

In the new organisation, it was service at the branch offices that would be the primary merit…[because] it was the branch offices that gave the bank its income [i.e. delivered value to clients, towards their purpose]

In the new organisation:

-

- the branch offices were the buyers of [enabling services]; and

- the [central] departments the sellers who needed to cover their costs.”

It’s one thing saying this. It’s quite another achieving it. So how did Wallander do it?

Put simply, he stopped ‘push to’ the front line and enabled ‘pull by’ the front line.

Initially, he wanted to ‘stop the train’:

“[Head office] Departments were forbidden to send out any more memos to the branch offices apart from those that were necessary for daily work and reports to the authorities [e.g. regulators].

[All the head office] committees and working groups engaged in various development projects…were told to stop their work at once and the secretaries were asked to submit a report on not more than one A4 page describing what the work had resulting in so far.”

Then he wanted to change the direction:

“An important tool in the change process was the creation of a central planning committee that had a majority of members representing the branch offices.

This committee summoned the managers of the various head office departments, who had to report on what they were planning to do… and how much it would cost the branch offices [i.e. what value would be derived].

The committee could then decide [what was of use to their clients] and [where they considered it was not] the departmental managers were sent back to do their homework again.

In short, those delivering to clients (the branch offices) were given ‘right of veto’ over those from elsewhere proposing changes to this.

This had a dramatic effect. If you are a central department and you don’t want to be wasting your time on unwanted stuff (and who does?), then you’d better (regularly) get out to the front line, observe what’s happening, understand what’s required and/or getting in the way, and then collaborate on helping to resolve.

Further, if (after doing this) a central department develops something that the branches don’t want to use, then the next step turns into dialogue (leading to deeper understanding and valuable pivots in direction), not enforcement.

…which would create adult – adult interactions (rather than parent – child).

The core of the organisational design

I’m going to set out a bunch of inter-related points that need to be taken together for their effect to take hold. Here goes:

I’m going to set out a bunch of inter-related points that need to be taken together for their effect to take hold. Here goes:

1. The local team ‘owns’ the client (relationship):

A client isn’t split up into lots of ‘bits’ and referred ‘all over the place’. Rather, the local team owns the client, as a whole person, throughout their journey. This provides: the client with direct access to the people responsible for helping them; and the local team with meaningful work.

“If you want people motivated to do a good job, give them a good job to do.” (Hertzberg)

2. The local team functions as a semi-autonomous self-managing unit, and is the primary unit of importance:

They are fully responsible for their local cohort of clients and, where they need to, pulling expertise to them (rather than pushing them off to other places).

3. The local team manager is a hugely important role:

This is because they are the linchpin (the vital link). They are responsible for:

- the meaningful and sustained help provided to their local cohort of clients;

- the development and wellbeing of the local team helping clients; AND

- ensuring that the necessary support is being pulled from (and being provided by) the enabling centre.

They are NOT the enforcers of the centre’s rules. Rather they are the stewards of their local community (clients and employees). This is a big responsibility…which means turning the ‘local team manager’ into a highly desirable role and promoting highly capable people into it.

In a reversal of thinking:

- the old way was that you ran a local site in the hope of one day moving ‘up’ to head office

- the new way is that a job at the centre might be a stepping-stone to being appointed as one of the highly respected local team managers

4. The capability of the local team employees is paramount:

If the local team are to truly help clients, then focused, ongoing time and effort needs to go into developing their capability to do this.

They are no longer merely ‘front line order takers’…so they need help to develop and grow (‘on the job’, ‘in the moment’).

5. Local team employees must receive a reasonable salary:

If we want people to develop and grow such that they deliver outstanding help to their clients, then we need to pay them accordingly. This is not ‘unskilled’ work (whatever that means nowadays).

Putting points 1 through to 5 together creates a virtuous circle: meaningful work, self-direction, relatedness, growth, wellbeing…and back around to meaningful work.

We now turn to some enabling principles:

6. The centre’s job is to enable (and NOT control) the local team:

Basically, re-read (if you need to) what I’ve written above about Wallander’s head office problem and how to transform this.

THE core principle here is that the local teams (via representation) have right of veto over central ideas for change. After all, YOU (the centre) are impacting upon THEIR clients.

For those of you ‘in the centre’ who are thinking “but this is Bullsh!t, the problem is that the local team just don’t get why [my brilliant change] is necessary!” then

- either they know something you don’t…and so you’d better get learning

- and/or you know something they don’t…and so you’d better get into a productive dialogue with them

…and whichever it is, a dose of experiential learning (at the Gemba) is likely to be the route out of any impasse.

In short: If the local team don’t ‘get it’ or don’t ‘want it’ then the centre has more work to do!

7. All employees (local team and centre) need clarity of purpose and a set of guiding principles:

Whilst we want each and every local team ‘thinking for itself’, we need them all to be going in the same direction. For this to occur, they need a simple, clear (client centred) purpose and principles, to use as their anchor for everything they do…and with this they can amaze us!

Which leads to one of my all-time favourite quotes:

“Simple, clear purpose and principles give rise to complex and intelligent behaviour.

Complex rules and regulations give rise to simple and stupid behaviour.” (Dee Hock)

We also need the ‘centre’ (and most definitely senior management) to live and breathe the purpose and principles*. Without this it’s just ‘happy talk’.

* Note: This list of nine points (and the context around them) is a good start on a core set of principles.

8. There needs to be transparency across local teams as to the outcomes being achieved (towards purpose):

A key role for the centre is simply to make transparent that which is being achieved, so that this is clear to all…and then resist dictating ‘answers’.

This means that each local team can see their outcomes and those of all the other local teams…and can therefore gain feedback, which creates curiosity, stimulates collaboration, generates innovation, and produces learning towards purpose…

…we are then on the way to a purpose-seeking organisation.

Once outcomes are transparent, then if the centre is demonstrably able to help, it is highly likely that local teams will pull for it.

Clarification: Transparency of systemic outcomes towards purpose, NOT activities and outputs (i.e. how many ‘widgets’ were shoved from ‘a’ to ‘b’ and how quickly!)

and last, but by no means least…

9. The budget process needs to be replaced with something better:

I’m not going to write anything detailed on this, as I’ve written about this before. You are welcome to explore this point if you wish: ‘The Great Budget God in the Sky’.

In short, the conventional budget process is also a HUGE problem for a system in meeting its client defined purpose.

Right, I’m one point short of ‘The Ten Commandments’…so I’ll stop there. This isn’t a religion 🙂

To close

The above might seem unpalatable, even frightening, to the current ‘Head Office machine’ but there’s still seriously important work for ‘the centre’ to do…but just different to how you do it now.

In fact, if those in the centre really thought about it (and looked at the copious evidence), how much of what the head office machine currently does provides truly meaningful and inspiring work for you? Perhaps not so much.

Sure, we tell ourselves that we’ve ‘delivered’ what we said we would, according to a budget and timescale…but how are those clients going? Are things (really) getting better for them, or are they stuck and perhaps even going backwards?

How would you know? I expect the local team could tell you!

Footnotes:

1. Historical context: Handelsbanken was, back at the end of the 1960s, a large historic Swedish bank that had got itself into an existential crisis

It was run in the typical functionalised, centralised command-and-control manner, according to the dominant management ideas emanating from American management schools (and which still leave a heavy mark on so many organisations today)

The Handelsbanken Board decided to headhunt a new CEO in an attempt to turn things around (i.e. ‘transform’ in the proper use of the word)

Dr. Jan Wallander was an academic who, through years of research and experience, had arrived at a systemic human-centred management philosophy. To test his thinking, he had taken up the role of CEO at a small Swedish bank (which was becoming an increasingly successful competitor of Handelsbanken)

The Handelsbanken Board were struck with the highly successful outcomes that Wallander had achieved, and they wanted him to rescue them from their crisis.

In 1970 he said yes to their request…but with strings attached: They had to allow him the time and space to put his ideas into practice.

2. ‘Local team’, ‘Branch’, ….: Organisations choose various words to refer to their local presence, be it office, site, shop, outlet, etc. What matters most is the decentralised thinking, not the word chosen or even how the ‘localness’ manifests itself.

I’ve used the generic phrase ‘local team’ in this blog because it implies (to me) a distinct group of people looking after their clients. You’ll note that Jan Wallander refers to the ‘Branch’ in this respect (which fits with his banking world). You can substitute any word you wish so long as it retains the point.

3. The detail for this post comes mainly from Jan Wallander’s book ‘Decentralisation – Why and How to make it work: The Handelsbanken Way’. It is an interesting (and relatively short) read.

I found this book a bit hard to get hold of. I got mine shipped from Sweden…though I had a little mishap of accidently procuring the Swedish language version – sadly, not much use to me and my limited linguistic skills. I happily amended my order to the English version.

4. ‘Within a community’: The conventional public sector model is to have a huge number of branches within a given community – one for each central government department, one for each separate NGO, etc. etc. They are (virtually always) at cross purposes with each other, causing vulnerable clients to have to adopt the inappropriate (and unacceptable) position of trying to ‘project manage’ themselves through the malaise.

The need is to replace this controlling central-ness (lots of central Octopuses with overlapping local tentacles) with meaningful local teams. This is a huge subject in itself, and worthy of another post (or a series of).

It’s very short Friday evening post time 🙂

It’s very short Friday evening post time 🙂

Have you ever thought about the types of ‘management books’ out there?

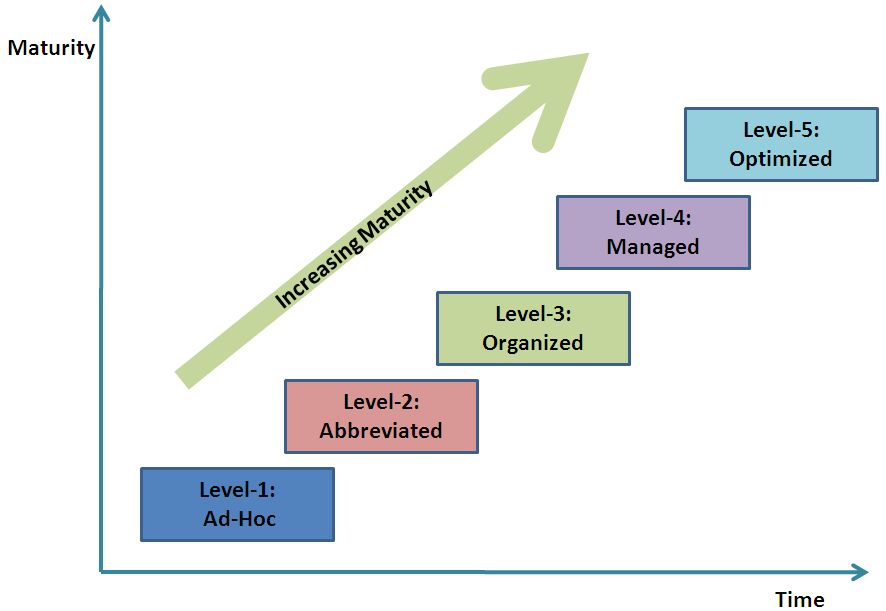

Have you ever thought about the types of ‘management books’ out there? …(so called) ‘maturity models’.

…(so called) ‘maturity models’. My recent serialised post titled

My recent serialised post titled  A positive example of this phenomenon: The All Blacks won the rugby World Cup in 2011 and 2015, making them the first team ever to achieve ‘back-to-back’ rugby World Cups. They did this with a core of extremely influential world-class players3…who then promptly retired!

A positive example of this phenomenon: The All Blacks won the rugby World Cup in 2011 and 2015, making them the first team ever to achieve ‘back-to-back’ rugby World Cups. They did this with a core of extremely influential world-class players3…who then promptly retired! So, staying with rugby, let’s move to the English national team. In contrast to the All Blacks, they have had two terrible World Cups.

So, staying with rugby, let’s move to the English national team. In contrast to the All Blacks, they have had two terrible World Cups.

I’ve been meaning to write this post for 2 years! It feels good to finally ‘get it out of my head’ and onto the page.

I’ve been meaning to write this post for 2 years! It feels good to finally ‘get it out of my head’ and onto the page. So, picture the scene: It’s the late 1970s. Your organisation desperately wants to improve and, on looking around for someone

So, picture the scene: It’s the late 1970s. Your organisation desperately wants to improve and, on looking around for someone  You helpfully provide training and (so called) ‘coaching’…and you put in place ‘governance’ to ensure it’s working. You roll it all up together and you give it a funky title…like your Quality Toolbox. Nice.

You helpfully provide training and (so called) ‘coaching’…and you put in place ‘governance’ to ensure it’s working. You roll it all up together and you give it a funky title…like your Quality Toolbox. Nice. So it’s now the 1990s. The methods and tools that came out of the initial Toyota factory visit weren’t sustained but the pressure is still on (and mounting) to transform your organisation…and your management can’t help noticing that Toyota are still doing amazing!

So it’s now the 1990s. The methods and tools that came out of the initial Toyota factory visit weren’t sustained but the pressure is still on (and mounting) to transform your organisation…and your management can’t help noticing that Toyota are still doing amazing! …and so to the 2000s. The pressure to change your organisation is relentless – the corporate world is ‘suffering’ from seemingly constant technological disruption…but Toyota continues to be somehow different.

…and so to the 2000s. The pressure to change your organisation is relentless – the corporate world is ‘suffering’ from seemingly constant technological disruption…but Toyota continues to be somehow different.