I regularly notice many service organisations1 communicate to the public with a list of facts that apparently demonstrate that their services are a good thing. This usually occurs at their reporting year-end and is titled something like “Our work this year”2.

I regularly notice many service organisations1 communicate to the public with a list of facts that apparently demonstrate that their services are a good thing. This usually occurs at their reporting year-end and is titled something like “Our work this year”2.

I call this the ‘didn’t we do well!’ comms.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m a big supporter of the concept of services that help people….and, yes, I’d like to know what these services are doing and how well this is going.

The problem, for me, is with the conventional approach to providing the public with ‘the evidence’…which goes something like this:

“This year we:

- handled x incoming contacts [calls, texts, webchats, emails….]

- made x outbound contacts [calls, texts, emails, letters,…]

- sent out x ‘things’ [advice leaflets, application forms, packs/kits, results…]

- received x referrals

- delivered x appointments

- provided x services

- paid out $x

- supported x people to achieve [things]”

- …and on and on and on

Every time I read such a set of facts (which is often funkily presented with fancy graphics and icons in carefully curated colours), I think “Okay, so you’ve done a lot of stuff this year, but…

- is this good, bad or indifferent?

- have you got better at doing this stuff? [#efficiency]

and most importantly…

- does this stuff actually deliver valuable outcomes to those you are serving?” [#effectiveness]

In short, when I look at the funky comms served up to us, I cannot tell whether the services ‘did well’…or not.

A bevy of big numbers!

You might say “but Steve, look at those big numbers!”

And I’d respond that, okay, you answered 2,000,000 calls this year! Of course that sounds a lot to me – I probably only answered 200 calls on my personal phone in the same period.

The average person is going to find the volumes that an organisation deals with unimaginable to them because, quite obviously, the organisation is operating at a profoundly different scale!

The issue is not that the number is big – it should be! – but what has been achieved? which leads me onto…

Activity vs. Capability Measures

The vast majority of big numbers published are measures of activity – volumes of things occurring.

Such measures do not tell the reader about how capable the organisation is, or the wider system that it exists within.

I’m minded of the phrase of people being “busy fools”3. Yes, you might all have been extremely busy, but busy achieving what?!

Starting with the purpose of the organisation, or the system in question, what measures would inform us as to how capable it is in meeting it?

- The purpose of an organisation is not to answer calls, send out forms, carry out appointments – these are activities.

- The purpose is to deliver the necessary value (what the organisation was set up for).

A tortuous illustration4:

Let’s put ourselves into the shoes of a human that has a need…

- We search online to see what services are available

- We find an appropriate website but can’t work out if/how our specific scenario fits so we call the advertised ‘advice line’. We are talked through some info. and emailed a link to an online form… We use this link and attempt to digitally apply for a service but we soon find that we first need a ‘customer ID’, so we request one of these and wait…

- The organisation receives our request to obtain a customer ID and this sits in a digital ‘task queue’, to be prioritised and allocated

- In the meantime, we call the organisation’s contact centre to chase up our request for a customer ID. The contact centre agent finds our request in the ‘task queue’. They go ahead and create a new account for us and email our customer ID to us so that we can continue…

- We sign in to the ‘App’ with our newly minted customer ID and continue with the application that we think meets our situation

- We try to fill in a long and detailed form on the App – it’s a bit confusing so there’s plenty of household banter about what each question is asking for and why.

- We get to the point where we call the organisation’s contact centre to check how to properly fill it in – we want to get it right because we really want our need to be met. After talking with (another) contact centre agent, we finally manage to complete and submit the form.

- We are sent via text an appointment slot that we must attend to discuss our application

- We can’t make this computer-determined day/time slot, so we have to call the appointment line to rebook to a slot that works for us

- The organisation then sends a letter to us confirming the revised appointment details, and stating that we must bring various documents with us

- We don’t understand the letter – it reads like ‘gobbledegook’ to most lay people – and so, given the elapsed time from ‘start to now’, we really need help…so we physically go to (and queue at) our local branch to clarify what the letter is attempting to say

- ….I could go on and on and on

But I’ll cut to the chase to use the partial illustration above to hopefully make the point:

The organisation can count up all the activities, and report that:

- their website had x hits

- their ‘App’ was used x times

- they took x calls

- they created x new client accounts

- they processed x application forms

- they held x appointments

- …and on and on and on

…and, yes, the hoards of activities show that they have been tremendously busy!

If, instead, we put ourselves in ‘customer’5 shoes and understand what matters to them6 in respect of the service meeting their need, we might come up with some potential measures of capability like the following:

| What matters | …meaning | Potentially measured by… |

| Time | It happens quickly: and

When I need it by |

End-to-end time from need first arising to its (customer defined) satisfaction

Whether the customer was disadvantaged by the time it took (e.g. missed an important event) |

| Easy | It was obvious what to do, and how to get it right first time

It takes minimal effort to achieve |

Whether the customer managed to get the initial ‘value step’ right first time

The number of subsequent steps in the process to achieve the customer’s need7 |

| Transparent | I understand what’s going to happen and by when

I understand what has happened and why |

Whether the customer chased as to what is going on

Whether the customer queried what has been done |

| Appropriate/ accurate outcome | It meets my need! | Whether/ how well the outcome met the customer’s need |

Now, measures like these would tell us interesting stuff!

I’d love to see capability measures8 for each and every service system that matters.

Further, I’d want the organisation to be using such measures so that they know how they are doing…rather than being blinded by those big ‘activity’ numbers.

Footnotes

1. Public services: including central government departments, local government councils, health services, education institutions, …etc. etc.

2. Examples: I’ve seen sooo many examples over the years and I could provide links to several. However, I don’t really want to ‘pick on’ any specific organisations – because the point is so widespread. Rather, can I suggest that you ‘keep your eyes out’ and see if you come across one in your world.

3. The brilliant header image is one angle of ‘The busy fool’ by artist John Clark. https://www.thestratfordgallery.co.uk/artists/john-clark/busy-fool/34975

4. The illustration: Just to be super clear…this is made up…though there’s an element of truth to all of it – coming from experiences that I’ve observed from various services over the years. Please note that I could have legitimately made it a lot worse!

Bear in mind that the poor customer in the scenario hasn’t even attended the appointment yet…there’s plenty more grief that can yet come their way…which will increase the ‘didn’t we do well’ activity measures.

5. Customer: generic for whatever is appropriate for the system in question – client, patient, student, traveller, detainee,…citizen, human.

6. What matters, and how best to measure against this, will be specific to each work system. It won’t be a generic set of attributes and measures that can be applied to everything. They need to be evidenced from understanding (studying) the customers of the given service.

7. Number of customer steps: My tortuous illustration lists 8 customer interactions…before they even have their interview.

8. Capability – The right measures: This post deals with the topic of ‘the right measures…’. Its twin topic is ‘…measured right’. A post on this would contrast the madness of binary comparisons (comparing two numbers) with viewing a measure over a period of time.

Governments all over the world want to get the most out of the money they spend on public services – for the benefit of the citizens requiring the services, and the taxpayers footing the bill.

Governments all over the world want to get the most out of the money they spend on public services – for the benefit of the citizens requiring the services, and the taxpayers footing the bill. He takes us through a case study of a real person in need, and their interactions with multiple organisations (many ‘front doors’) and how the traditional way of thinking seriously fails them and, as an aside, costs the full system a fortune.

He takes us through a case study of a real person in need, and their interactions with multiple organisations (many ‘front doors’) and how the traditional way of thinking seriously fails them and, as an aside, costs the full system a fortune. He identifies three survival principles in play, and the resulting anti-systemic controls that result:

He identifies three survival principles in play, and the resulting anti-systemic controls that result: Cox makes the obvious point that the actual redesign can’t be explained up-front because, well…how can it be -you haven’t studied your system yet!

Cox makes the obvious point that the actual redesign can’t be explained up-front because, well…how can it be -you haven’t studied your system yet! [Once you’ve successfully redesigned the system] “The primary focus is on having really good citizen-focused measure: ’are you improving’, ‘are you getting better’, ‘is the demand that you’re placing reducing over time’.”

[Once you’ve successfully redesigned the system] “The primary focus is on having really good citizen-focused measure: ’are you improving’, ‘are you getting better’, ‘is the demand that you’re placing reducing over time’.” I’ve written enough posts now to

I’ve written enough posts now to  The outcome of their research project was the concept of a Balanced Scorecard of measurements (and, of course, the accompanying Harvard Business School (HBS) management book).

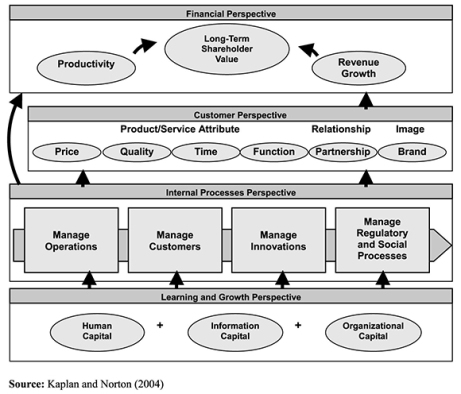

The outcome of their research project was the concept of a Balanced Scorecard of measurements (and, of course, the accompanying Harvard Business School (HBS) management book). The ‘Strategy Map’ turned the four quadrants of the balanced scorecard into a linear cause-effect view (see picture)

The ‘Strategy Map’ turned the four quadrants of the balanced scorecard into a linear cause-effect view (see picture) Example: Can I manage how employees feel? Yes, by how I behave.

Example: Can I manage how employees feel? Yes, by how I behave.

Senior Management’s beliefs and behaviours determine (i.e. cause) the management system that they choose to put into effect and (often stubbornly) retain;

Senior Management’s beliefs and behaviours determine (i.e. cause) the management system that they choose to put into effect and (often stubbornly) retain; Okay – let’s suppose that senior management accept that measures aren’t everything and that we shouldn’t be balancing (let alone weighting) things – I hope that we can all agree that some

Okay – let’s suppose that senior management accept that measures aren’t everything and that we shouldn’t be balancing (let alone weighting) things – I hope that we can all agree that some  My recent serialised post titled

My recent serialised post titled  A positive example of this phenomenon: The All Blacks won the rugby World Cup in 2011 and 2015, making them the first team ever to achieve ‘back-to-back’ rugby World Cups. They did this with a core of extremely influential world-class players3…who then promptly retired!

A positive example of this phenomenon: The All Blacks won the rugby World Cup in 2011 and 2015, making them the first team ever to achieve ‘back-to-back’ rugby World Cups. They did this with a core of extremely influential world-class players3…who then promptly retired! So, staying with rugby, let’s move to the English national team. In contrast to the All Blacks, they have had two terrible World Cups.

So, staying with rugby, let’s move to the English national team. In contrast to the All Blacks, they have had two terrible World Cups.

The ending of Chapter 1 was about Money power and, in particular, the idea of Dead Money provided by professional financiers – people focused on profit.

The ending of Chapter 1 was about Money power and, in particular, the idea of Dead Money provided by professional financiers – people focused on profit. If you’ve not read it then I heartily recommend a well written book by Ha-Joon Chang (Economics Professor at Cambridge) called ’23 Things they don’t tell you about Capitalism’3.

If you’ve not read it then I heartily recommend a well written book by Ha-Joon Chang (Economics Professor at Cambridge) called ’23 Things they don’t tell you about Capitalism’3. Ha-Joon Chang goes on to tear apart the 1980s principle of ‘shareholder value maximisation’ (I won’t reproduce his critique here…but it is well worth reading4).

Ha-Joon Chang goes on to tear apart the 1980s principle of ‘shareholder value maximisation’ (I won’t reproduce his critique here…but it is well worth reading4). No, I’m not.

No, I’m not. Don’t they need barrow loads of private financier’s money?

Don’t they need barrow loads of private financier’s money?

I came across a LinkedIn ‘research’ report that had been shared on a social media platform the other day. It had a grand title:

I came across a LinkedIn ‘research’ report that had been shared on a social media platform the other day. It had a grand title: It’s a bit like all those scientific research projects spending scarce grant money to confirm that ‘water quenches our thirst’ or ‘alcohol gets us drunk’ or [insert one from today’s supposed news].

It’s a bit like all those scientific research projects spending scarce grant money to confirm that ‘water quenches our thirst’ or ‘alcohol gets us drunk’ or [insert one from today’s supposed news]. I often hear people talking about the need for profit and that my thinking must address this fact. I respond that it does, but not as they might think. This post tries to explain.

I often hear people talking about the need for profit and that my thinking must address this fact. I respond that it does, but not as they might think. This post tries to explain. Many an organisation spends a great deal of time and money on the re-branding band wagon. Some outcomes are good, others not so good…and many fit into the ‘huge waste of money’ bucket.

Many an organisation spends a great deal of time and money on the re-branding band wagon. Some outcomes are good, others not so good…and many fit into the ‘huge waste of money’ bucket. So I’ve written a few posts to date about

So I’ve written a few posts to date about