So I came across a PowerPoint slide recently that was headed something like ‘Deming’s 14 points for management translated for our organisation today’ (emphasis added).

So I came across a PowerPoint slide recently that was headed something like ‘Deming’s 14 points for management translated for our organisation today’ (emphasis added).

It then contained 14 very brief (i.e. 2 or 3 word) phrases of unclear meaning.

I am familiar with Deming’s 14 points for management, having them on my wall, and many (most?) of the phrases on the PowerPoint slide were alien to me.

Now, the reasons for this apparent mismatch could be one, or many, of the following. The author of the slide:

- doesn’t understand Deming’s principles; or

- doesn’t agree with Deming; or

- doesn’t think that they apply to his/her organisation or to the world as it stands today1; or

- does understand, does agree with them and does think they are applicable BUT doesn’t want to ‘upset the applecart’ with the inconvenient truth that some (many?) of Deming’s principles might go completely against how his/her organisation currently operates2

…and so considers it necessary and acceptable to, let’s say, ‘adjust’ them.

Now, the point of this post is not to dwell on my translation concerns on what I read on a PowerPoint slide (I mean no disrespect or malice to the writer). The point is to faithfully set out Deming’s 14 points as he wrote them and to pull out some pertinent comments…and, in so doing, to point out where many organisations have a way to go.

“Hang on a minute Steve…

…erm, you seem to be suggesting that Deming’s points are akin to a holy book! What’s so important about what Deming had to say?!”

If you are wondering who on earth Dr W. Edwards Deming was then please have a read of my earlier ‘about the giants’ post on Deming.

In short, he may be considered a (the?) father figure for post war Japan/ Toyota/ Lean Thinking/ Vanguard Method/ Operational Excellence…and on and on. If you believe you are on a ‘Lean Thinking’ journey, then Deming is a hugely important figure and I’d humbly suggest that anyone/everyone study and understand his thinking.

So, here they are!

Deming’s 14 points for management, as summarised3 by Deming (the blue italics), with additional comment from me4:

“The 14 points are the basis for transformation. It will not suffice merely to solve problems, big or little. Adoption and action on the 14 points are a signal that management intend to stay in business and aim to protect investors and jobs…

…the 14 points apply anywhere, to small organisations as well as to large ones, to the service industry as well as to manufacturing.

1. Create constancy of purpose towards improvement of product and service, with the aim to become competitive and to stay in business, and to provide jobs.

Purpose is about improvement for the customer, not growth and profitability per se. If we constantly pursue our customer purpose, then success (through growth and profitability) will result …NOT the other way around. You have to act as you say, the stated purpose cannot be a smokescreen.

2. Adopt the new philosophy. We are in a new economic age. Western management must awaken to the challenge, must learn their responsibilities, and take on leadership for change.

Deming’s reference to Western management might now be referred to as ‘Command and control’ management and ‘management by the numbers’. Not all of western management today is command and control (there are many great organisations that have escaped its grip using Deming’s wise words) and, conversely, command and control is not limited to the west – it has sadly spread far and wide.

It’s a philosophy: Deming isn’t putting forward an action plan. He’s putting forward an aspirational way of being. The distinction is important.

3. Cease dependence on inspection to achieve quality. Eliminate the need for inspection on a mass basis by building quality into the product in the first place.

“Quality cannot be inspected into a product or service; it must be built into it” (Harold S Dodge). If you have lots of ‘controls’, then you need to consider root cause – why do you deem these necessary?

Controls cannot improve anything; they can only identify a problem after it has occurred. What to do instead? The answer lies (in part) at point 12 below.

4. End the practise of awarding business on the basis of price tag. Instead minimise total cost. Move towards a single supplier for any one item, on a long-term relationship of loyalty and trust.

How many suppliers (such as outsourcing and IT implementations) are selected on the basis of a highly attractive competitive tender and are then paid much much more once they have jammed their foot in the door, and the true costs emerge once we have become reliant on them?

True strategic partnerships beat a focus on unit prices.

5. Improve constantly and forever the system of production and service, to improve quality and productivity, and thus constantly decrease costs.

The starting point and never-ending journey is quality, in the eyes of the customer. The outcome (result) will be decreasing costs. Cause and effect.

To start at costs is to misunderstand the quality chain reaction. Focussing on cost-cutting paradoxically adds costs and harms value.

6. Institute training on the job.

Management (of ALL levels) need constant education at the gemba and, when there, need to understand capability measurement and handle (not frustrate) variation.

7. Institute leadership. The aim of supervision should be to help people and machines and gadgets to do a better job. Supervision of management is in need of overhaul, as well as supervision of production workers.

Management should be farmers, not heroes.

8. Drive out fear, so that everyone may work effectively for the company.

The fixed performance contract (incorporating targets and rewards) is management by fear. Replace with trust.

9. Break down barriers between departments. People in research, design, sales and production must work as a team, to foresee problems of production and in use that may be encountered with the product or service.

This doesn’t mean turn everything on its head! Many an organisation misunderstands and attempts a grand re-organisation from vertical silos to horizontal streams. This is not the point. There is a need for (appropriate) expertise – the problem are the barriers that prevent collaboration across such teams….such as cascaded objectives, targets, rewards, competitive awards…and on.

10. Eliminate slogans, exhortations, and targets for the workforce asking for zero defects and new levels of productivity. Such exhortations only create adversarial relationships, as the bulk of the causes of low quality and low productivity belong to the system and thus lie beyond the power of the work force.

The role of management is to improve the environment that people work within, rather than constantly badger and bribe people to do better.

11.

a) Eliminate work standards (quotas) on the factory floor. Substitute leadership.

b) Eliminate management by objective. Eliminate management by numbers, numerical goals. Substitute leadership.

Numeric targets and straight jacket rules do not improve processes. On the contrary – they create dysfunctional behaviour that clashes with ‘serve customer’ as people struggle to survive.

12.

a) Remove barriers that rob the…worker of his right to pride of workmanship. The responsibility of supervisors must be changed from sheer numbers to quality.

b) Remove barriers that rob people in management and in engineering of their right to pride of workmanship. This means, inter alia, abolishment of the annual or merit rating and of management by objective

This means removal of the performance review process!

To improve, the value-adding workers need to be given the responsibility to measure, study and change their own work. This fits with the front-line control (devolution) lever.

13. Institute a vigorous program of education and self-improvement

i.e. learn about Deming, about all the other giants …but through education, not merely training; through educators, not gurus….and then experiment.

14. Put everybody in the company to work to accomplish the transformation. The transformation is everybody’s job.”

…but don’t fall into the ’empowerment’ trap! Empowerment cannot be ‘given’ to teams, or people within…it can only be ‘taken’…and they will only take it if their environment motivates them to want to, for themselves.

True collective accountability (i.e. where everyone can and wants to work together towards the same common purpose) comes from profit sharing within an ideal-seeking system.

Beware ‘making a message palatable’

Going back to that translation: Some of you may argue back at me that the person that carefully ‘translated’ Deming’s 14 points into something more palatable is ‘working with management’ and ‘within the system’ and that this is the best thing to do.

I don’t subscribe to this way of thinking (and neither did/do the giant system thinkers such as Ohno, Ackoff, Scholtes, Seddon etc.)

To borrow a John Seddon quote:

“Fads and fashions usually erupt with a fanfare, enjoy a period of prominence, and then fade away to be supplanted by another. They are typically simple to understand, prescriptive, and falsely encouraging – promising more than they can deliver. Most importantly fads and fashions are always based on a plausible idea that fits with politicians and management’s current theories and narratives – otherwise they wouldn’t take off.”

Beware the trap of ‘adjusting’ an unpalatable message (to the current status quo) in an attempt to progress. In making it ‘fit’ with management’s current thinking you will likely have bleached the power from within it.

For example: to translate Deming’s point 12 and (conveniently) omit his words around abolishing management by objectives and the performance rating system is to (deliberately) strip it of its meaning. Sure, it’s been made ‘agreeable’ but also worthless.

Deming’s philosophy is no fad or fashion! As such, it is important that it shouldn’t be treated that way. Managers should be exposed to what he said and why…and those that are true leaders will pause for self-reflection and curiosity to study their system, to get knowledge as to what lies within.

Footnotes:

1. Deming wrote about the 14 points in his 1982 book ‘Out of the Crisis’

2. If this is the reason then it strongly suggests that the organisation fails on Deming’s point 8: Management by fear.

3. Whilst this is only Deming’s summary, he wrote in detail on each point i.e. if you want a deep understanding of one (or all) of them then you can.

4. There’s far too much to pull out of the above to do justice to Deming within this one post – I’ve merely scratched the surface!…and, if you have been a reader of this blog for a while, you will likely have read enough that supports most (all?) of his points.

I was listening to some seasonal ‘organisational comms’ when I noticed two words being used in a way that felt problematic – they were being used the wrong way around. I’ve come to view the two words as important1 so their usage ‘stood out’ and made me pause for thought.

I was listening to some seasonal ‘organisational comms’ when I noticed two words being used in a way that felt problematic – they were being used the wrong way around. I’ve come to view the two words as important1 so their usage ‘stood out’ and made me pause for thought.

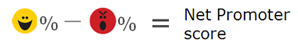

Have you heard people telling you their NPS number? (perhaps with their chests puffed out…or maybe somewhat quietly – depending on the score). Further, have they been telling you that they must do all they can to retain or increase it?1

Have you heard people telling you their NPS number? (perhaps with their chests puffed out…or maybe somewhat quietly – depending on the score). Further, have they been telling you that they must do all they can to retain or increase it?1 You then work out the % of your total respondents that are Promoters and Detractors, and subtract one from the other.

You then work out the % of your total respondents that are Promoters and Detractors, and subtract one from the other. “Management thinking affects business performance just as an engine affects the performance of an aircraft. Internal combustion and jet propulsion are two technologies for converting fuel into power to drive an aircraft.

“Management thinking affects business performance just as an engine affects the performance of an aircraft. Internal combustion and jet propulsion are two technologies for converting fuel into power to drive an aircraft.  You will tell your manager what you think he/she wants to hear, and provide

You will tell your manager what you think he/she wants to hear, and provide  So I came across a PowerPoint slide recently that was headed something like ‘Deming’s 14 points for management translated for our organisation today’ (emphasis added).

So I came across a PowerPoint slide recently that was headed something like ‘Deming’s 14 points for management translated for our organisation today’ (emphasis added).