There’s a lovely idea which I’ve known about for some time but which I haven’t yet written about.

There’s a lovely idea which I’ve known about for some time but which I haven’t yet written about.

The reason for my sluggishness is that the idea sounds so simple…but (as is often the case) there’s a lot more to it. It’s going to ‘mess with my head’ trying to explain – but here goes:

[‘Heads up’: This is one of my long posts]

Learning through feedback

We learn when we (properly) test out a theory, and (appropriately) reflect on what the application of the theory is telling us i.e. we need to test our beliefs against data.

“Theory by itself teaches nothing. Application by itself teaches nothing. Learning is the result of dynamic interplay between the two.” (Scholtes)

Great. So far, so good.

Single-loop learning vs. Double-loop learning

Chris Argyris (1923 – 2013) clarified that there are two levels to this learning, which he explained through the phrases ‘single-loop’ and double-loop’1.

Here are his definitions to start with:

Single-loop learning: learning that changes strategies of action (i.e. the how) …in ways that leave the values of a theory of action unchanged (i.e. the why)

Double-loop learning: learning that results in a change in the values of theory-in-use (i.e. the why), as well as in its strategies and assumptions (i.e. the how).

That’s a bit of a mouthful – and (with no disrespect meant) not much easier to comprehend when you read his book!2

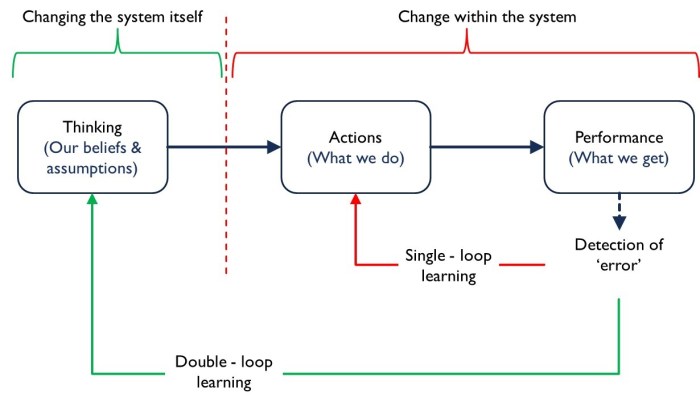

If you look up ‘double loop learning’ on the wonders of Google Images, you will find dozens of (very similar) diagrams3, showing a visualisation of what Argyris was getting at.

Here’s my version4 of such a diagram:

You can think about this diagram as it relates either to an individual (e.g. yourself) or at an organisational level (how you all work together).

Start at the box on the left. Whether we like it or not, we (at a given point in time) think in a certain way. This thinking comes about from our current beliefs and assumptions about the world (and, for some, what might lie beyond).

Our thinking guides our actions (what we do), and these actions heavily influence5 our performance (what we get).

And so to the ‘error’ bit:

“Organisations [are] continually engaged in transactions with their environments [and, as such] regularly carry out inquiry that takes the form of detection and correction of error.” (Argyris & Schon)

We are continually observing, and inquiring into, our current outcomes – asking ourselves whether we are ‘on track’, or everything is ‘as we would expect’ or perhaps whether we could do better. Such inquiry might range from:

- subconscious and unstructured (e.g. just part of daily work); right through to

- deliberate and formal (such as a major review producing a big fat report).

Argyris labels this constant inquiry as the ‘detection of error’. The error is that we aren’t where we would want to be, and the correction is to do something about this.

Okay, so we’ve detected an error and we want to make a corrective change. The easiest thing to do is to revisit our actions (and the strategies that they are derived from), and assess and develop new action strategies whilst keeping our underlying thinking (our beliefs and assumptions) steadfastly constant. This is ‘single-loop’ learning i.e. new actions, borne from the same thinking.

I reflect that the phrase ‘the more things change, the more they stay the same’ fits nicely here:

If the reason for the ‘error’ is within your thinking, then your single-loop learning, and the resultant change, won’t work. Worse, you will re-observe that error as it ‘comes round again’, and probably quicker this time…and so you make another ‘action’ change….and that error keeps on coming around. You have merely been making changes within the system, rather than changing the system.

A previous post called ‘making a wrong thing righter’ demonstrates this loop through the example of short term incentive schemes, and their constant revision “to make them even better”.

So, the final piece of the diagram…that green line. Many ‘errors’ will only be corrected through inquiry into, and modification of, our thinking…and, if this meaningfully occurs, then this would result in ‘double-loop’ learning – you would have changed the system itself.

Right, so that’s me finished explaining the difference between single-loop and double-loop learning…which I hope is clear and makes sense.

You may now be thinking “great, let’s do double-loop learning from now on!”

…because this is how most (if not all) those Google Image diagrams make it look. I mean, now you know about it, why wouldn’t you?

But you can’t!

The bit that’s missing…

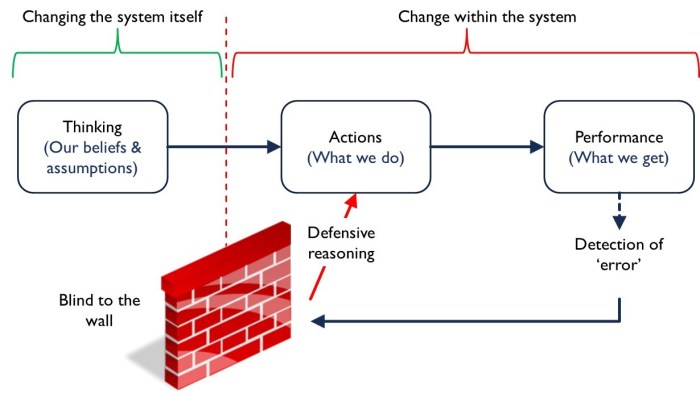

Unfortunately, there’s a wall. Worse still, this wall is (currently) invisible. Here’s the diagram again, but altered accordingly:

Right, I’d better try and explain that wall. Argyris & Schon wrote that:

“People learn collectively to maintain patterns of thoughts and action that inhibit productive learning.”

What are they on about?

Imagine that, through some form of inquiry, an error (as explained above) has been detected and a team of relevant people commence a conversation to talk about it:

- The hierarchically senior person begins with a ‘take charge’ attitude (assuming responsibility, being persuasive, appealing to larger pre-existing goals);

- it is typical within organisations that, once goals have been decided, changing them is seen as a sign of weakness.

- it is typical within organisations that, once goals have been decided, changing them is seen as a sign of weakness.

- He/she request a ‘constructive dialogue’, thereby stifling the expression of negative (yet real) feelings by themselves, and by everyone else involved…and yet acts as if this is not happening;

- each person in the group is therefore being asked to “suppress their feelings – to experience them privately, censor them from the group, and act as if they are not doing so.”

- each person in the group is therefore being asked to “suppress their feelings – to experience them privately, censor them from the group, and act as if they are not doing so.”

- He/she takes a rational approach and asks the group to develop a ‘credible plan’ (which becomes the objective) to respond to the error…and so has skipped the necessary organisational self-reflection for double-loop learning to occur.

- Coming up with a plan is ‘jumping into solution mode’ before you’ve properly studied the current condition and asked ‘why’.

- Coming up with a plan is ‘jumping into solution mode’ before you’ve properly studied the current condition and asked ‘why’.

So how does this affect the group dynamics?

“The participants experience an interest in solving the business problem, but their ways of crafting their conversation, combined with their self-censorship, [will lead] to a dialogue that [is] defensive and self-reinforcing.” (Argyris & Schon)

Given that this approach will hide so much, we can expect lots of private conversations (pre-meetings to prepare for meetings, post-meetings about what was/wasn’t said in meetings, meetings about what meetings aren’t happening…). Does this describe what you sometimes see in your organisation? I think that it is often labelled as ‘politics’…. which would be evidence of that wall.

Taken together, Argyris and Schon label the above as primary inhibitory loops.

Argyris sets out a (non-exhaustive) list of conditions that trigger and, in turn, reinforce, such defensive and dysfunctional behaviour. Here’s the list of conditions, together with how they should be combated:

| Condition | Corrective response |

| Vagueness | Specify |

| Ambiguity | Clarify |

| Un-test-ability | Make testable |

| Scattered Information | Concert (arrange, co-ordinate) |

| Information withheld | Reveal |

| Un-discuss-ability | Make discussable |

| Uncertainty | Inquire |

| Inconsistency/ Incompatibility | Resolve |

”[such] conditions…trigger defensive reactions…these reactions, in turn, reduce the likelihood that individuals will engage in the kind of organisational inquiry that leads to productive learning outcomes.” (Argyris & Schon)

i.e. If you’ve got defensive behaviour, look for these conditions… and work on correcting them. Otherwise you will remain stuck.

Unfortunately, primary loops lead to secondary inhibitory loops. That is, that they lead to second-order consequences, and these become self-reinforcing.

- Managers begin to (privately) judge their staff poorly, whilst the staff, ahem, ‘return the compliment’, with “both views becoming embedded in the organisational norms that govern relationships between line and staff”;

- Sensitive issues of inter-group conflict become undiscussable. “Each group sees the other as unmovable, and both see the problem as un-correctable.”

- A classic example of this is the constant conflict in many organisations between ‘IT’ and ‘The business’.

- A classic example of this is the constant conflict in many organisations between ‘IT’ and ‘The business’.

- The organisation creates defensive routines “intended to protect individuals from experiencing embarrassment or threat” …with the unintended side effect that this then prevents the identification of “the causes of the embarrassment or threat in order to correct the relevant problems.”

From this we get organisational messages that:

- are inconsistent (in themselves and/or with other messages);

- act as if there is no inconsistency; and

- make the inconsistency undiscussable.

“The message is made undiscussable by the very naturalness with which it is delivered and by the absence of any invitation or disposition to inquire about it.”

Do you receive regular messages from, say, those ‘above you’ in the hierarchy? Perhaps a weekly or monthly Senior Manager communication?

- How often are you amazed (in an incredulous way) about what they have written or said?

- Do you feel welcome to point this inconsistency out? Probably not.

We end up with people giving others advice to reinforce the status quo: ‘Be careful what you say’, ‘You’ll get yourself into trouble’, ‘I wouldn’t say that if I were you’, ‘Remember what happened last time’…etc.

In short, there are powerful forces* at work in most organisations that are preventing (or at least seriously impeding) productive learning from taking place, despite the ability and intrinsic desire of those within the organisation to do so.

(* Note: Budgets – as in fixed performance contracts – are a classic ‘single-loop reinforcing’ management instrument. Conversely, Rolling forecasts can be a ‘double-loop’ enabler.)

So what to do instead?

Right, here’s my third (and last) diagram:

It looks very similar to the last diagram, but this time there’s a ladder! But where do we get one of those from?

“For double-loop learning to occur and persist at any level in the organisation, the self-fuelling processes must be interrupted. In order to interrupt these processes, individual theories-in-use [how we think] must be altered.” (Argyris & Schon)

Oooh, exciting stuff! They go on to write:

“An organisation with a [defensive] learning system is highly unlikely to learn to alter its governing variables, norms and assumptions [i.e. thinking] because this would require organisational inquiry into double-loop issues, and [defensive] systems militate against this…we will have to create a new learning system as a rare event.”

There’s two places to go from here:

- What would a productive learning system look like? and

- How might we jolt the system to see the wall, and then attempt to climb the ladder?

If I can begin to tease these two out, then BINGO, this blog post is ready for print. Right, nearly there…

A Productive learning system

Argyris and Schon identify three values necessary for a productive learning system:

- Valid information;

- Free and informed choice; and

- Internal commitment to the choice, including constant monitoring of its implementation.

Sounds lovely…but such a learning system requires the fundamental altering of conventional social virtues that have been taught to us since early in our lives. The following table ‘compares and contrasts’ the conventional with the productive:

| Social Virtue: | Instead of… | Work towards… |

| Help and Support | Giving approval and praise to others, and protecting their feelings | Increasing others capacity to confront their own ideas, and to face what they might find. |

| Respect for others | Deferring to others, and avoiding confronting their actions and reasoning. | Attributing to others the capacity for self-reflection and self-examination. |

| Strength | Advocating your position in order to ‘win’, and holding firm in the face of advocacy. | Advocating your position, whilst encouraging inquiry of it and self-reflection. |

| Honesty | Not telling lies, or

(the opposite) telling others all you think and feel. |

Encouraging yourself and others, to reveal what they know yet fear to say. Minimising distortion and cover-up. |

| Integrity | Sticking to your principles, values and beliefs | Advocating them in a way that invites enquiry into them. Encouraging others to do likewise. |

There’s a HUGE difference between the two.

The consequences will be an enhancement of the conditions necessary for double-loop learning – with current thinking being surfaced, publicly confronted, tested and restructured – and therefore increasing long-term effectiveness.

You’d likely liberate6 a bunch of great people, and create a purpose-seeking organisation.

Intervention

The first task is for you to see yourself – you have to become aware of the wall…and Argyris & Schon are suggesting that you may (likely) require an intervention (a shake) to do this. Your current defensive learning system is getting in the way.

Let’s be clear on what would make a successful intervention possible, and what would not.

An interventionist would locate themselves in your system and help you (properly) see yourselves…and coach you through contemplating what you see and the new questions that you are now asking…and facilitate you through experimenting with your new thinking and making this the ‘new normal’. This is ‘action learning’.

This ‘new normal’ isn’t version 2 of your current system. It would be a different type of system – one that thinks differently.

Conversely, you will not change the nature of your system if you attempt to ‘get someone in to do it to you’.

Why not?

“Kurt Lewin pointed out many years ago that people are more likely to accept and act on research findings if they helped to design the research, and participate in the gathering and analysis of data.

The method he evolved was that of involving his subjects as active, inquiring participants in the conduct of social experiments about themselves.” (Argyris & Schon)

In short: It can’t be done to you.

That ladder? That would be a skilled interventionist, helping you see and change yourselves through ‘action learning’.

To Close

Next time someone shows you that lovely (as in ‘simple’) double-loop learning diagram, I hope you can tell them about the wall…and the ladder.

Footnotes

1. Chris Argyris is known as one of the co-founders of ‘Organisation Development’ (OD) – the study of successful organizational change and performance. Argyris notes that he borrowed the distinction between single-loop and double-loop from the work of W. Ross Ashby. For blog readers, we met Ashby in an earlier post on requisite variety.

2. Book: ‘Organisational Learning II: Theory, Method, and Practise’ (1996) by Chris Argyris and Donald A. Schon).

3. Diagrams: Many of the diagrams stay true to what Argyris wrote about. Some attempt to build upon it. Others (in my view) bastardise it completely!

4. Language: I should note that Argyris used different language to my diagram. Here’s a table that compares:

| My diagram: | Argyris and Schon: |

| Thinking (Our beliefs and assumptions) | Values, norms and assumptions |

| Action | Action Strategies |

| Performance | Performance, effectiveness |

| Defensive learning system | Model O – I |

| Productive learning system | Model O – II |

5. Influence: I haven’t used the bolder ‘cause’ word because there’s a lot going on that is outside the system (e.g. the external environment).

6. Liberate: You don’t need to bring in ‘new’ people, most of what you need are already with you – they just need liberating from the system that they work within.

7. Kurt Lewin: often referred to as ‘the founder of social psychology’. Much of my writings in this blog are based around Lewin’s equation that B= ƒ(P, E) or, in plain English, that behaviour is a function of the person in their environment.

If you are a systems thinking

If you are a systems thinking  Okay, you cynic….but are you?

Okay, you cynic….but are you? Erm, I’ll have to think about that one…

Erm, I’ll have to think about that one… Let me critique that label for a moment…

Let me critique that label for a moment… 4. “Passionate: Having, showing, or caused by strong feelings or beliefs”

4. “Passionate: Having, showing, or caused by strong feelings or beliefs” Oh yes, once my colleague and I thought we had finished our ‘labelling’ journey, we realised that nothing had actually changed. And so we turn to:

Oh yes, once my colleague and I thought we had finished our ‘labelling’ journey, we realised that nothing had actually changed. And so we turn to:

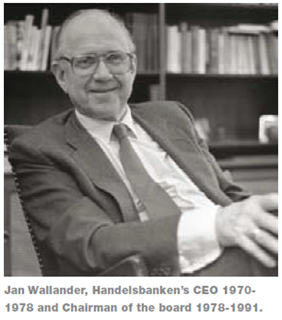

He took on the role of Handelsbanken’s CEO in 1970 and got stuck in to doing things quite differently! As an example, he was particularly scathing about budgets:

He took on the role of Handelsbanken’s CEO in 1970 and got stuck in to doing things quite differently! As an example, he was particularly scathing about budgets: So I was in a meeting. A colleague spoke up and said that she felt that incentives weren’t a good thing, that they caused much damage and that it would be better to remove their use and replace them with something better.

So I was in a meeting. A colleague spoke up and said that she felt that incentives weren’t a good thing, that they caused much damage and that it would be better to remove their use and replace them with something better.