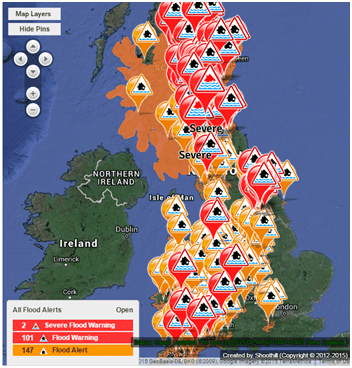

So, it’s coming to the end of December 2015 and the UK is reeling from torrential rain storms and, as a result, unprecedented flooding across circa. half the nation.

So, it’s coming to the end of December 2015 and the UK is reeling from torrential rain storms and, as a result, unprecedented flooding across circa. half the nation.

It makes for a really interesting case study of systems.

As a reminder, a system is “a network of inter-dependant components that work together to try to accomplish the aim of the system” (Deming)

Now the UK’s rain water dispersal system has many components, such as:

- the high ground on which the majority of the rain falls on;

- the small streams from which it flows downwards;

- the lakes and rivers in which it gathers;

- the flood plains on which the water spreads out;

- the man-made structures (banks, bridges, culverts, tunnels, protection barriers) put in place to ‘guide’ the water through major towns and cities; and finally

- down to the estuaries which feed into the sea

…and all along these components lays humanity and its man-made assets (domestic and commercial).

We all know that there is variation in rain-fall (though in the UK the rain switch seems to be more often in the ‘on’ rather than ‘off’ position) and that there are sometimes special events. Unfortunately the UK has experienced record breaking rainfall…

…and the system is unable to cope without having a drastic effect on people.

The UK Environment Agency (EA) has the unenviable task of protecting people and their possessions. They have spent years, and billions of pounds, building flood defences.

The outcome of the rain, whilst somewhat grisly for those involved, provides lots of examples of behaviour that is optimal for one component but catastrophic for another.

How about these:

Sand-bagging around your house: This is at the smallest end of the scale and sounds sensible and innocuous doesn’t it. What’s not to like?

Sand-bagging around your house: This is at the smallest end of the scale and sounds sensible and innocuous doesn’t it. What’s not to like?

Well, let’s say that you successfully sand-bag around your gate…where does the water go now?

…next door! This sets off a chain reaction. As each person sand-bags their door, then the volume of water that has been ‘turned away’ increases, making the poor bugger who hasn’t managed to plug their hole enough to become deluged with everyone else’s diverted problem; which takes us up the scale to…

The Fosse Barrier was built to protect the City of York from the River Ouse. Once closed, it prevents the River Ouse from forcing flood waters back up the tributary River Fosse and into the City of York, whilst simultaneously pumping the River Fosse around the barrier and into the River Ouse. Sounds tricky!

The Fosse Barrier was built to protect the City of York from the River Ouse. Once closed, it prevents the River Ouse from forcing flood waters back up the tributary River Fosse and into the City of York, whilst simultaneously pumping the River Fosse around the barrier and into the River Ouse. Sounds tricky!

The barrier was lowered a few days ago but, due to concerns about the unexpectedly high waters flooding (and thereby seizing up) the barrier mechanism, the EA took the (brave and/or daft?) decision to lift the barrier before this could occur…and thus knowingly flooded parts of York…although, by their calculations, reducing flooding elsewhere.

Here’s a picture of York after the River Fosse burst its banks:

…and on to an even bigger example:

- The Jubilee River is an artificial channel that was dug (at a cost of £110m) to divert flood waters from the River Thames around the towns of Maidenhead and Windsor. It was opened in 2002 and, given that it rejoins the River Thames below these towns, those residents unlucky to be downstream are seriously unhappy about it!

Here are a couple of quotes from angry residents “It’s grossly unfair that a man-made river can be to the benefit of some people and to the detriment of others.” and “I believe we are being used as sacrificial lambs!”

…and so what might the EA’s answer to this be? Well, to extend the scheme of course! “We have very extensive plans to continue the Jubilee River all the way down…to Teddington…It’s very expensive but it’s got huge support.” I bet it does – by those who will benefit! Erm, but won’t that just move the problem again?

Now, the EA can build walls and divert rivers the length and breadth of the land…and we can be certain that each engineered ‘solution’ will uncover the need for yet another one nearby. But what about reasons as to why the flooding is soooo bad this time? Is it about more than the volume of rain falling?

Here’s an interesting article written by George Monbiot on the subject (it’s aptly called ‘Going downhill fast’). Rather than trying to cope with the water once it’s got into our rivers, he looks at why it is rushing at such speeds to get there…such as:

- down from all that high ground that used to have trees on it (which massively soak up and contain water) but which have been cleared for grazing, grouse shooting and other such uses; and

- over all that land that has been concreted for industrial, commercial and domestic purposes.

The point:

Now, the above is in no way an attempt to advise the UK EA on what to do! I am merely using it all as a superb example of a complex and dynamic system, with all its various components.

I often talk about two excellent systems effects/ analogies and they are brilliantly demonstrated above:

- ‘Systems bite back’ and

- ‘The push down, pop up’ or ‘balloon effect’: “squashing down on activity in one place causes it to pop up somewhere else”

The whole point of systems thinking is to recognise that everything in the system is connected and interacts, usually in highly complex and unexpected ways…and in so realising, move our thinking to the ‘whole system’ level, rather than its components.

In the words of Indira Gandhi “Whenever you take [what you think is] a step forward, you are bound to disturb something.”

…and so it is the same within any organisation, and its value streams.

Organisational value streams

Each of our value streams are like the UK rain water dispersal system: they have a purpose, a start and end, and many components in between.

To manage at a component level is to cause problems elsewhere.

We can only truly improve a value stream (the system) when we think about it from end-to-end, understand it’s purpose from the customer’s point of view and fully collaborate along its full horizontal length….and, to do this, we need to remove any and all system conditions and management thinking that are impediments.

So I moved house a few months ago and I’ve been really slow at updating my address details with all those organisations that have wheedled their way into my life – I am suffering from the well known condition called ‘Post Office redirection service’ apathy.

So I moved house a few months ago and I’ve been really slow at updating my address details with all those organisations that have wheedled their way into my life – I am suffering from the well known condition called ‘Post Office redirection service’ apathy.