So, a bloody good mate of mine manages a team that delivers an important public service – let’s call him Charlie. We have a weekly coffee after a challenging MAMIL 1 bike ride….and we thoroughly explore our (comedic) working lives.

So, a bloody good mate of mine manages a team that delivers an important public service – let’s call him Charlie. We have a weekly coffee after a challenging MAMIL 1 bike ride….and we thoroughly explore our (comedic) working lives.

And so to our most recent conversation – Charlie told me that his department is due an inspection (a public sector reality)…and how much he, ahem, ‘loves’ such things! 🙂

“Oh, and why’s that?” I say.

His response2 went something like this: “Well, they come in with a standardised checklist of stuff, perform interviews and site visits to tick off against a set of targets, and then issue a report with our score, and recommendations as to what we should be doing….it’s not exactly motivational!”

“Mmm” I say…”but presumably their intent – to understand how well things are going – is good?”

Here’s the essence of Charlie’s reply: “Yep, I ‘get’ the intent behind many of the items on their checklist, and I accept that knowing how we are doing is really important…but, rather than act like robotic examiners, I want them to:

- understand us, and our reality (what we are having to deal with3)…and I want them to focus on what really matters in respect of our service, not hide behind narrow ‘currently trendy’ targets and initiatives set from above;

- give us the chance to demonstrate:

- how we are doing;

- where we know we have room for improvement; and

- what we are doing to get better; and finally

-

assist us, by adding value (perhaps with useful references to what they’ve seen working elsewhere) rather than be seen as ‘taking up our time’. “

“Righto”, I said ”…that sounds excellent! I’ll write a post on that lot”…so here goes:

A ‘short but sharp’ generic critique of inspections:

Inspection requires someone looking for something (whether positive or negative)…and this comes from a specification as to what they believe you should be doing and/or how you should be doing it.

Inspection requires someone looking for something (whether positive or negative)…and this comes from a specification as to what they believe you should be doing and/or how you should be doing it.

The ‘compliance’ word fits here.

…and, as such, the inputs, behaviours and outcomes from inspections are rather predictable. You can expect some or all of the following:

- people, often (usually?) from outside your service, spend time writing (often inflexible) specifications as to what you should (and should not) be doing;

- people are employed, and trained, as inspectors of those specifications;

- you and your team spend precious time preparing before each imminent inspection:

- running preparatory meetings to guess what might happen;

- window-dressing solely for the benefit of ‘the inspector’ e.g. making your work space look temporarily good, filling in (and perhaps even back dating) ‘paperwork’;

- even performing ‘dummy runs’ (rehearsals!);

- you and your team serenade the inspector around during their visit, with everyone on their best behaviour;

- questions are asked, careful (guarded) answers are given, and an inspection report is issued;

- your post-inspection time is then consumed rebutting (what you consider to be) poorly drawn recommendations and/or drafting action plans, stating what is going to be implemented to comply.

…and after it’s all over, a big sigh is let out, and you go back to how you were.

Wouldn’t it be great if, rather than playing the ‘inspection game show’, you truly welcomed someone (anyone) coming in to see what you actually do and, when they arrive, you carried on as normal because you are confident that:

- you are operating in the way that you currently believe to be the best; and

- you want them to see and understand this, and yet provide you with feedback that you can ponder, experiment with, and get even better at delivering against your purpose4.

…so how might you get to this wonderland?

A better way:

I’m a huge fan of a (deceptively) simple yet (potentially) revolutionary idea put forward by John Seddon:

I’m a huge fan of a (deceptively) simple yet (potentially) revolutionary idea put forward by John Seddon:

“Instead of being measured on compliance, people should be assessed on whether they are able to show that they are working to understand and improve the work they do.

It is to shift from ‘extrinsic’ motivation (carrot and stick) to intrinsic motivation (pride), which is a far more powerful source of motivation.”

…and to the crux of what Seddon is suggesting:

“Inspection of performance should be concerned with asking only one question of managers:

‘What measures are you using to help you understand and improve the work?’ “

This, to me, is superb – the inspector doesn’t arrive with a detailed checklist and ‘cookie cutter’ answers to be complied with; and the manager (and his/her team) has to really think about that question!

To answer it, the team must become clear on:

- the (true) purpose of the service that they provide;

- what measures5 would tell them how they are doing against this purpose (i.e. their capability);

- how they are doing against purpose (i.e. as well as knowing what to measure, they must be actively, and appropriately, measuring it for themselves);

- what they are working on to improve, and how these are affecting the performance of their system; and

- …what fresh ideas have arisen to experiment with.

You can see that this isn’t something that is simply ‘prepared in advance’ for a point-in-time inspection. It is an ongoing, and ever maturing, endeavour – a way of working.

It means that any inspector (or interested party) can arrive at any time and explore the above in use (as opposed to it being beautifully presented in ‘this years’ audit file ring-binder)

“Are you saying that ‘specifications’ are wrong then?”

Before ending this post, I’d like to clarify that:

Before ending this post, I’d like to clarify that:

- No, I’m not saying that specifications are (necessarily) wrong; and

- I’m also not saying that scientific know-how, generated from a great deal of experience over time should be ridiculed or ignored ‘just because it comes from somewhere else’.

Taking each in turn,

- Specifications (e.g. the current best known way to perform a task) should be owned by the team that have to perform them…and these should be:

- of adequate depth and breadth to enable anyone and everyone to professionally perform their roles;

- suitably flexible to cater for the variety of demands placed upon them (requiring principled guidelines rather than concrete rules); and

- ‘living’ i.e. continuously improved as new learning occurs6

-

If there is a central function, then their role should be to:

- understand what is working ‘out there’; and

- effectively share that information with everyone else (thus being of great value to managers)

…without dictating that a specific method should be ‘complied with’.

The point being that we should not think in terms of ‘best practise’…we should be continuously looking for, and experimenting with, better practise, suited to each scenario. This is to remove the (attempted) authority from the centre, and place it as the (necessary) responsibility where the actual work is performed, by the service (manager, and team) on the front line.

In this way, ‘the centre’ can shift itself from being seen as an interfering, bureaucratic and distant police force, to a much valued support service.

To Ponder:

If you are ‘being inspected’ then, yes, I ‘get’ that you currently need to ‘tick those boxes’…but how about thinking a little bit differently:

…how would you show those ‘inspecting you’ that you truly understand, and are improving, your system against its purpose?

You could seriously surprise them!

If you can really answer that one question, then you are likely to be operating a stable, yet continually improving service within a healthy environment, both for your team and those they serve.

Who knows – ‘the inspector’ might want to share what you are doing with everyone else 🙂

And, going back to the top – i.e. Charlie’s reply as to what he really wanted out of an inspection – I reckon he was ‘right on the money’!

A final comment…for all you private sector organisations out there:

Don’t think that this post doesn’t apply to you!

If you have centralised ‘Audit’, ‘Quality Assurance’ and/or ‘Business Performance’ teams (i.e. that are separate from the actual work), then virtually everything written above applies to your organisation.

Footnotes:

1. MAMIL: Middle aged men in lycra

2. To ‘Charlie’ – Please excuse the poetic licence that I have taken in writing the above…and I hope it may be of some use (woof woof 🙂 ).

3. What we are really dealing with: I picked the ‘Inspector Clouseau’ picture to allude to the possibility (probability?) that many an inspector, stuck with their heads in their audit checklist, hasn’t a clue about what is really going on within, and/or what really matters for, the service before them….and for some, this is still true AFTER the inspection has been completed 😦

I’m not trying to ‘shoot at’ inspectors – this is a role that you have (currently) been given. You might also like to ponder the above and thereby look to re-imagine your purpose. Doing so could dramatically improve your work satisfaction…and help improve the services that you support.

4. Purpose: not to be confused with the lottery of attempting to meet a numeric target.

5. A set of Measures that uncover how the system is performing, NOT one supposedly ‘all seeing’ KPI and an associated target.

6. Living: Years of (regularly futile) experience have proven to me that ‘learning aids’ (whether they be documents, diagrams, charts, pictures….) will only ‘live’ (i.e. improve) if they are regularly (i.e. necessarily) used by the workers to do the work. An earlier post (Déjà vu) fits here.

7. I think that a couple of previous posts are foundational and/or complimentary to this one:

The Principle of Mission: That clarification of intent, and allowing flexibility in how it is achieved, is far more important than waiting for, and slavishly carrying out ‘instructions’ from above.

Rolling, rolling, rolling: The huge, and game-changing difference between rolling out and rolling in change. One is static, the other is dynamic and purpose-seeking.

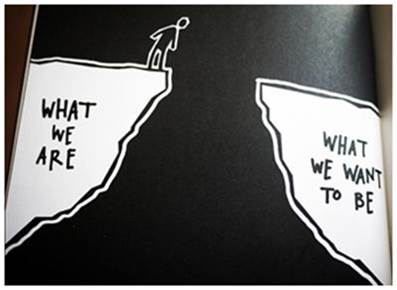

So it’s the beginning of an ‘Improvement through Systems Thinking’ course that I facilitate and I am asked a question from one of the attendees:

So it’s the beginning of an ‘Improvement through Systems Thinking’ course that I facilitate and I am asked a question from one of the attendees: Are you interested in crossing that divide?

Are you interested in crossing that divide?

Being a pom, I hadn’t heard the ‘suck it up’ phrase until I came to New Zealand. I find it quite amusing…I particularly like some of its derivatives like ‘harden up’ and ‘take a concrete pill’.

Being a pom, I hadn’t heard the ‘suck it up’ phrase until I came to New Zealand. I find it quite amusing…I particularly like some of its derivatives like ‘harden up’ and ‘take a concrete pill’.