So I recently had a most excellent conversation with a comrade.

So I recently had a most excellent conversation with a comrade.

I’d written some guff in the usual way and he wanted to push back on it…great! I need to be challenged on my thinking, particularly the more I verbalise (and therefore risk believing) it.

His push back:

I’d used the ‘absorb variety’ [in customer demand] phrase yet again…and he (quite rightly) said “but what does it mean?”

He went on to say that, whilst he understands and agrees with a great deal of what I write about, he doesn’t fully agree with this bit. He has reservations.

So we got into a discussion about his critique, which goes something like this:

“I agree that we should be customer focused, but…‘absorb their variety’???

You can’t do anything for everybody….they’d start asking for the world…you’d go out of business! There have to be rules as to what we will or won’t do.”

He gave an example:

“If a customer asked you to fax them their documents [e.g. invoice, contract, policy…], surely you’d say no because this is such old technology and it doesn’t make sense for people to use it anymore.”

Yep, a very fair view point to hold…and an example to play with.

So, in discussing his critique, I expanded on what I mean when using the ‘absorb variety’ phrase. Here’s the gist of that conversation:

First, be clear as to what business you are in

Taking the “you can’t do anything for everybody” concern: I agree…which is why any business (and value stream within) should be clear up-front on its (true) purpose.

However, such a purpose should be written in terms of the customer and their need. This is important – it liberates the system from the ‘how’, rather than dictating method. It allows flexibility and experimentation.

Clarification: ‘liberating’ doesn’t mean allowing anything – it means a clear and unconstrained focus on the purpose (the ‘why’ for the system in question). If you don’t have a clear aim then you don’t have a system!

Understanding the customer: who they are, what they need.

Okay, so the purpose is set, but each customer that comes before us is different (whether we like this or not). The generic purpose may be the same, but what works best for each unique customer and their specific situation will have nuances.

Okay, so the purpose is set, but each customer that comes before us is different (whether we like this or not). The generic purpose may be the same, but what works best for each unique customer and their specific situation will have nuances.

On ‘unique’: A service organisation (or value stream within) may serve many customers, but a customer only buys one service – their need. We need to see the world through their eyes.

“The customer comes in customer-shaped” (John Seddon)

Let’s take the scenario of an insurer handling a house burglary, with some contents stolen and property damage from the break-in.

The customer purpose of ‘help me recover from my loss’ is generic yet focused…it clearly narrows down what the value stream is about.

But, at the risk of stereotyping, here’s some potential customer nuances:

- Fred1 is an old person that lives at home alone. He’s very upset and concerned about his security going forward;

- Hilary is a really busy person and just wants the repair work done to a high quality, with little involvement required from her;

- Manuel2 doesn’t speak English very well;

- Theresa is currently away from the country (a neighbour notified the police);

- ….and the variety goes on and on and on3

Each of these customers needs to recover from their loss…but the specifics of what matters differ and these can be VERY important to them.

If we (are ‘allowed’ by our management system4 to) make the effort up-front to (genuinely) understand the customer and their specific unit of demand, and then work out how best to meet their needs then they are going to be very happy…and so are we…AND we will handle their need efficiently.

If we don’t understand them and, instead, try to force them into a transaction orientated strait-jacket, we can expect:

…adding significant and un-necessary costs and damaging our reputation. Not a great place to work either!

Do what is ‘reasonable’ for them

Right, so you may agree that we should understand a customer and their reality…but I still hear the critique that we can’t do anything and everything for them, even if it could be argued as fitting within the purpose of the value stream in question.

So let’s consider the ‘what’s reasonable?’ question. ‘Reasonable’ is judged by society, NOT by your current constraints. Just because your current system conditions5 mean that you can’t do it doesn’t make it unreasonable!

A test: if you (were allowed to actually) listen to the customer, understand the sense in their situation and the reasonableness of their need…but respond with “computer says no” (or such like) then your value stream isn’t designed to absorb variety.

A test: if you (were allowed to actually) listen to the customer, understand the sense in their situation and the reasonableness of their need…but respond with “computer says no” (or such like) then your value stream isn’t designed to absorb variety.

And so we get to what it means to design a system that can absorb variety.

It doesn’t mean that we design a hugely complicated system that tries to predict every eventuality and respond to it. This would be impossible and a huge waste.

It means to design a system that is flexible and focuses on flow, not scale. This will be achieved by putting the power in the hands of the front-line worker, whilst providing them with, and allowing them to pull, what they need to satisfy each customer and their nominal value. This is the opposite of front-line ‘order takers’ coupled to back-office specialised transaction-oriented sweat shops.

How does that ‘fax request’ example sit with the above? Well, on its own, I don’t know…and that’s the point! I’d like to know why the customer wants it by fax.

- perhaps they aren’t in their normal environment (e.g. they are on holiday in the middle of nowhere) and the only thing available to them is some old fax machine;

- perhaps they didn’t know that we can now email them something;

- perhaps they don’t (currently) trust other forms of communication…and we’d do well to understand why this is so;

- perhaps, perhaps perhaps…

Each scenario is worthy of us understanding them, and trying to be reasonably flexible.

Forget all that!

Of course the above means virtually nothing.

Of course the above means virtually nothing.

You’d need to see the variety in your system for yourself to believe, and understand, it…and the way to do that would be to listen and see how your current system DOESN’T absorb variety.

How would you do that? Well, from listening to the customer:

- in every unit of failure demand;

- within each formal complaint made to you;

- …and from every informal criticism made ‘about you’ (such as on social media)

I’ve got absolutely no idea what you would find! But do you?

The funny thing is…

…if we allow front-line/ value-creating workers to truly care about, and serve each customer – as individuals – in the absence of ‘management controls’ that constrain this intent (e.g. activity targets) then:

- the ‘work’ becomes truly inspiring for the workers, ‘we’ (the workers) gain a clear purpose with which we can personally agree with and passionately get behind;

- we become engaged in wanting to work together to improve how we satisfy demand, for the good of current and future customers; and

- the ‘management controls’ aren’t needed!

If I asked you, as a human being:

- do you primarily care about, say, a ‘7 day turn-around target’? (other than to please management/ get a bonus)

vs.

- do you really want to help Fred (or Hilary, Manuel, Theresa…) resolve their specific needs and get back on with their lives?

…how would you answer?

We need to move away from what makes sense to the attempted industrial production of service delivery to what makes sense in the real worlds of the likes of Fred.

Footnotes

1. Fred: The picture of Fred comes from a most excellent blog post written by Think Purpose some time ago. This post really nicely explains about the importance of understanding customer variety in a health care setting.

2. Manuel: A tribute to the late Andrew Sach (a.k.a Manuel from Fawlty Towers) who died recently. He wasn’t very good at English…

3. Variety in service demand: I’ve previously written about Professor Frances Frei’s classification of five types of variety in service demand and, taken together, they highlight the lottery within the units of demand that a service agent is asked to handle.

4. Allowed to: This is not a criticism of front-line workers. Most (if not all) start by wanting to truly help their customers. It is the design of the system that they work within that frustrates (and even prevents) them from doing so.

You show me a bunch of employees and I’ll show you the same bunch that could do awesome things. Whether they do so depends!

5. System Conditions may include structures, policies, procedures, measures, technology, competencies…

6. Bespoke vs. Commoditisation: It has been put to me that there are two types of service offerings. Implied within this is that there are two distinct customer segments: One that wants little or no involvement for a low cost and another that wants, and is willing and able to pay for, a bespoke service.

This is, for me, far too simplistic and misunderstands customer variety. Staying with the world of insurance…

A single customer might want low involvement when managing their risk (taking out a policy and paying for it, say, ‘online’) but to deal with a human if they need help recovering from a loss (i.e. at claim time).

That same customer may switch between wanting low involvement and the human touch even within a value stream – e.g. happy with low involvement car insurance but wants a human when it comes to their house insurance.

…and even within a given unit of demand, a customer may be happy with low involvement (say registering a claim)…but want the option of a human conversation if certain (unpredictable) scenarios develop.

The point is that we shouldn’t attempt to pigeon-hole customers. We should aim to provide what they need, when they need it…and they will love us for it!

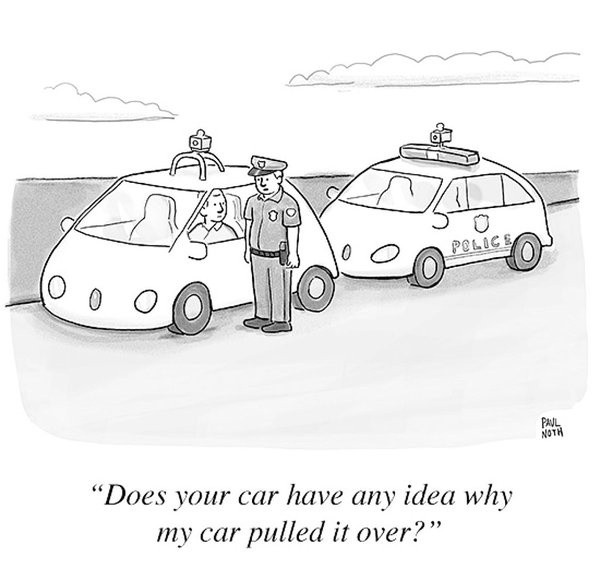

7. Automation: On reading the above, some of you may retort with “Nice ideas…but you’re behind the times ‘Granddad’ – the world has moved to Artificial Intelligence and Robotics”. I wrote about that a bit back: Dilbert says… lets automate everything!

A recurring theme, as felt by me as a ‘customer’ of many services, is that the front-line person (apparently) ‘helping me’ with my need(s) has treated me like an idiot.

A recurring theme, as felt by me as a ‘customer’ of many services, is that the front-line person (apparently) ‘helping me’ with my need(s) has treated me like an idiot.

This short post is about receiving text messages from service organisations: Some are (or could be) useful, whilst many others are (ahem) ‘bullshit masquerading as customer care’.

This short post is about receiving text messages from service organisations: Some are (or could be) useful, whilst many others are (ahem) ‘bullshit masquerading as customer care’. Aaaargh! That’s about as much use as a chocolate fire guard. It gives me no information of value. They have quite brilliantly engineered a near certain

Aaaargh! That’s about as much use as a chocolate fire guard. It gives me no information of value. They have quite brilliantly engineered a near certain  Here’s what the second text said:

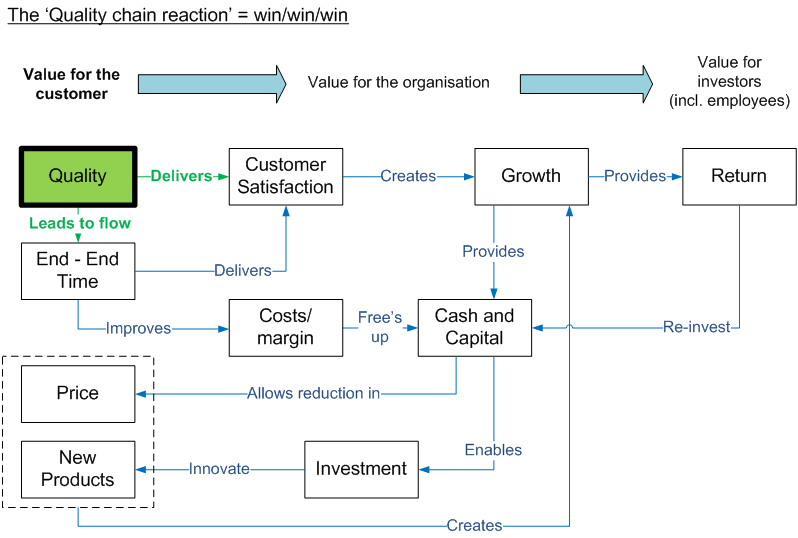

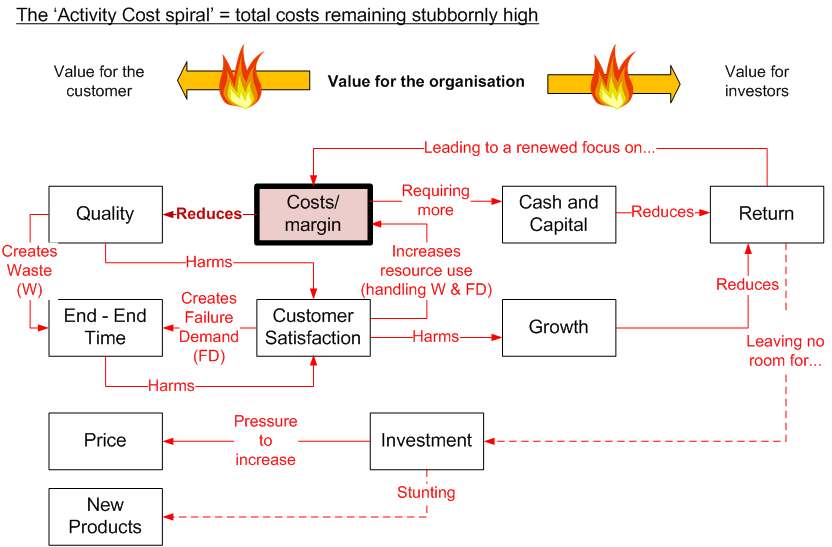

Here’s what the second text said: Followers of ‘Modern’ (?) management find themselves in essentially the same position: Trying to increase value1 to their investors. But,

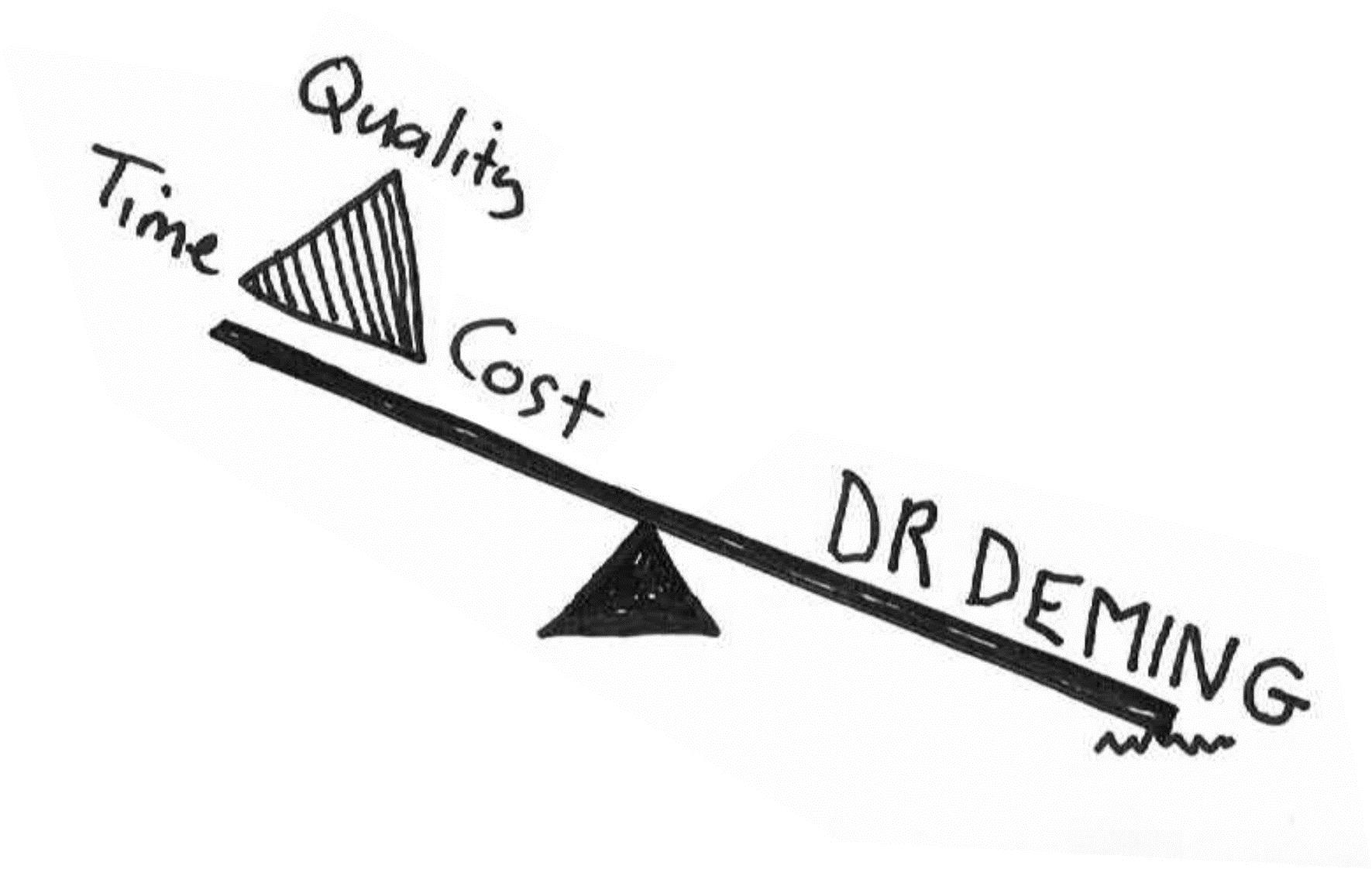

Followers of ‘Modern’ (?) management find themselves in essentially the same position: Trying to increase value1 to their investors. But,  It will go on to suggest that the Project Manager’s job is to juggle these three variables so as to deliver ‘on time, within budget and to an acceptable quality’.

It will go on to suggest that the Project Manager’s job is to juggle these three variables so as to deliver ‘on time, within budget and to an acceptable quality’.

So I recently had a most excellent conversation with a comrade.

So I recently had a most excellent conversation with a comrade. Okay, so the purpose is set, but each customer that comes before us is different (whether we like this or not). The generic purpose may be the same, but what works best for each unique customer and their specific situation will have nuances.

Okay, so the purpose is set, but each customer that comes before us is different (whether we like this or not). The generic purpose may be the same, but what works best for each unique customer and their specific situation will have nuances. A test: if you (were allowed to actually) listen to the customer, understand the sense in their situation and the reasonableness of their need…but respond with “computer says no” (or such like) then your value stream isn’t designed to absorb variety.

A test: if you (were allowed to actually) listen to the customer, understand the sense in their situation and the reasonableness of their need…but respond with “computer says no” (or such like) then your value stream isn’t designed to absorb variety. Of course the above means virtually nothing.

Of course the above means virtually nothing.

I absolutely love ‘Dilbert’ – it seems to me that Scott Adams, the cartoonist, has seen into our very souls when it comes to our working lives.

I absolutely love ‘Dilbert’ – it seems to me that Scott Adams, the cartoonist, has seen into our very souls when it comes to our working lives.