Most of us who have been on some form of management course will likely have heard of ‘Theory X and Theory Y Management’. You may groan and say “oh no, not that old theory…I’ve never used it for anything” or “you’re a bit behind the times…we’ve all moved on since then!”

Most of us who have been on some form of management course will likely have heard of ‘Theory X and Theory Y Management’. You may groan and say “oh no, not that old theory…I’ve never used it for anything” or “you’re a bit behind the times…we’ve all moved on since then!”

The more I look back at the early work on management, the more I believe that they contain profound foundations for what has come since. Let me explain.

A short history lesson (taken from Scholtes ‘The Leaders Handbook’ and Handy’s ‘Understanding Organisations’):

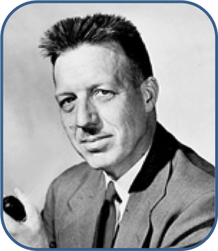

- Douglas McGregor’s father and grandfather were ministers;

- His grandfather founded a homeless shelter in Detroit during the 1930s depression;

- A young Douglas worked in the shelter alongside his father and grandfather.

Douglas and his father held very different views on the people they assisted, something that they would argue about.

- His father held negative views towards the unemployed and homeless, considering them shifty and lazy etc;

- Conversely, Douglas considered the poor to be no different from others, just that they were simply down on their luck and victims of a terrible economic situation.

As Douglas grew older, his thinking evolved into his famous 1960s articulation of Theory X and Theory Y assumptions about workers.

Theory X:

- The average human being has a natural dislike of work, and will work as little as possible;

- He/she lacks ambition, wishes to avoid responsibility and prefers to be led;

- He/she is by nature resistant to change but is gullible and not very bright;

Because of these characteristics, most people must be coerced, controlled, directed or threatened so as to modify their behaviours to fit the needs of the organisation.

The above might be said to require a ‘command and control’ style of management.

Theory Y:

- The expenditure of physical and mental effort in work is as natural as play or rest;

- People will exercise self-direction and self-control in the service of objectives to which they are committed;

- The motivation, potential for development, capacity to assume responsibility, and readiness to direct behaviour towards organisational goals, are all present in people;

- The capacity to exercise a relatively high degree of imagination, ingenuity and creativity towards organisational problems is widely, not narrowly, distributed in the population.

It is the responsibility of management to arrange the conditions and methods of operation so that people can achieve their own goals best by directing their own efforts in alignment with the purpose of the organisation.

The above matches the teachings of W Edwards Deming and what has been labelled a ‘Systems Thinking’ management system.

The point: McGregor was NOT writing about two different types of people. His theory was about two sets of assumptions made about people.

We can see that this will be a self-fulfilling prophecy. If management apply Theory X assumptions to their people (commanding and controlling them), then they can expect to see Theory X behaviours in return. This is cause and effect.

People are not, by nature, passive or resistant to working towards the organisation’s purpose. They have become so as a result of the management system that they experience.

Conversely, if management provides an environment that allows systems thinking, collaboration, interesting work content and choice through self direction, then we can expect Theory Y assumptions to become a reality.

A clarification: Theory Y still requires a clear sense of organisational direction (purpose) and systemic structure (though not necessarily hierarchical).

As an aside:

- I always see a flaw in Theory X assumptions. It requires manager and worker to be two different sub-species of human beings. Otherwise the theory is disproved by contradiction – if, for example, people don’t like responsibility but managers do, then they can’t be the same human variety!;

- Conversely, I see that Theory Y fits with one human genus. It works no matter where you are positioned within an organisation’s system.

Actions speak louder than words: Now, you will likely say “…but leaders always talk about their ‘Theory Y’ assumptions”….and, yes, I realise that this is so…this is what they (rightly) think the people want to hear.

But are their actions the opposite? What about the management instruments of cascaded personal objectives, arbitrary numeric targets , contingent rewards , and the rating and ranking of people’s ‘performance’.

A subtle, yet massive implication: If leaders use carrots and/or sticks then they are subscribing to Theory X assumptions about their people….otherwise carrots and sticks would make no sense.

A thought-provoking quote from Scholtes:

“Behind incentive programs lies management’s patronising and cynical set of assumptions about workers….Managers imply that their workers are withholding a certain amount of effort, waiting for it to be bribed out of them.”