I’ve worked with several service organisations that have adopted (what are referred to as) Tiered service models for their service design…and I’ve written about some of the problematic implications.

I’ve worked with several service organisations that have adopted (what are referred to as) Tiered service models for their service design…and I’ve written about some of the problematic implications.

Some specific recent posts to mention in this regard are:

- The Supermarket Shelf analogy;

- ‘Bob the Builder’: Push vs. Pull analogy; and

- The ‘Spaghetti notes’ phenomenon.

You might think that I have a problem with the idea of ‘tiered services’…and you’d be right (at least as they are conventionally enacted).

You might then ask “okay, but what instead?”

Good question! This (longer) post is some opening thoughts on that.

Setting the context within which I am writing:

It’s worth stating up front that the ‘service sector’ is a broad church. There’s a difference between you:

- selecting and then buying an item, such as a tangible book or a digital streaming service [ref. transactional need];

- engaging with a builder to renovate an aspect of a house, such as the bathroom [ref. process need]; and

- requiring some form of help to deal with/ change/ recover from some aspect(s) of your life1 [ref. relational need]

As usual, I’m mainly focused on the last one…which seems to be ‘butchered’ in many a conventional service design.

What is ‘Case Management’ supposed to be about?

Case Management is a phrase that is thrown around within service organisations all the time…and yet it is rarely well defined as to what it ought to be/do.

So, I’ll start at the start…

Definition of a ‘Case’:

- “An instance of disease or injury [ref. the health field]

- A suit or action in law [ref. the legal field]

- A situation requiring investigation or action [ref. the police field]

In general: “Case is used to direct attention to an occurrence or situation that is to be considered, studied, or dealt with.” Plain English: A situation needing action. (Source: Merriam Webster Dictionary)

Note that an alternative meaning of the word ‘Case’ is:

- “a box or receptacle for holding something”; or

- “an outer covering or housing”

…which we can see as related to the primary definition in that it is a container for a thing.

Okay, so if that’s what a ‘Case’ is, what’s a ‘Case Manager’?

There are loads of long-winded definitions ‘out there’ from various Case Management Societies (which exist all around the world), so I thought I’d look for a simple dictionary definition to start with…

“A person (e.g. social worker or nurse) who assists in the planning, co-ordination, monitoring, and evaluation of medical services for a patient with emphasis on quality of care, continuity of services, and cost-effectiveness.” (Source: Merriam Webster Dictionary)

Some points worth noting from this definition:

- the original2 use of the phrase ‘Case Manager’ would appear to be the medical field;

- it is about a person overseeing the whole case – ref. planning, co-ordinating, monitoring, evaluating – i.e. someone taking responsibility for the case;

- quality is referenced…which, by definition, is determined (and its attainment decided upon) by the client3;

- continuity of service is specifically referenced (i.e. that the role is stable and enduring).

Corollary: You don’t really have case managers if the system design ‘passes clients around’ as things change. The whole point of a case manager is to handle the uncertain and changing picture!

- Cost effectiveness: note the word effectiveness, not efficiency.

Ref. Performance Measurement – A guide | Squire to the Giants

And so we get to ‘Case Management’…

I think that ‘things got muddy’ when Information Technology introduced ‘Case Management’ software applications…because a ‘Case’ became a computer record, and ‘Case Management’ often then became about ‘the computer running business rules’ to tell people what they should be doing (#Tasking).

- On the use of computers: It makes absolute sense to digitally capture, organise and present case information…and therefore replace paper files…but such applications shouldn’t butcher the fundamental point of ‘case management’.

i.e. that there is someone who (really) understands what’s going on, who is working hard to help, and who is monitoring and evaluating to pivot accordingly (#complexity #variety #variation #emergence).

And then there’s something called ‘Integrated Case Management’, which seems to have become the ‘new thing’. Two potential causes (as I currently see it):

- as if trying to cope with the demise of ‘traditional’ case management…so a new phrase was needed to rebadge the original meaning; and/or

- integrating case management across multiple fields (i.e. the whole)

- e.g. Medical with Social with Legal with…

Right, that hopefully sets out the basis for true Case management. Let’s get back to that ‘tiered’ thingy…

What is a ‘Tiered service model’?

Using the magic of Google, I get various websites providing basically the same definition…so I’ll paraphrase them to:

A tiered service model is a structured approach to [service design], where incoming service requests are categorised [ref. ‘Triaged’ 🙂 ], and ‘streamed’ to specific tiers based on matching the complexity of need to the expertise required to manage.

Further, requests are escalated up the tiers if [it turns out that] greater expertise is required.

There are several important consequences arising from this reasoning:

|

Consequences of: |

Problems arising: |

|

Categorisation |

Up-front categorisation is based on unclear and incomplete information…which often can’t be known ‘up front’. i.e. it’s not a case of perfecting the ‘intake’ step…because it can’t be. Sure, make it ‘as good as possible’…but relevant information will always emerge (as trust is gained4, and as things change) |

|

‘Streaming’ |

No matter how many different ‘specialised teams’ we create or how well we define rules as to ‘what should go where’:

|

|

Escalation (& subsequent de-escalation) |

A high degree of movement of cases around (and around) the tiers due to the non-linear and uncertain:

This is in addition to disagreements between the tiers about what should be going where (“that shouldn’t be one of ours…let’s move it to their queue”) |

|

Duplication and/or ‘falling through the gaps’ |

We get:

|

|

Treating a ‘service request’ as a transaction rather than a person |

Seeing the ‘service request’ as a simple thing to do, rather than entangled with the person and everything else that’s going on for them. |

In a tiered service model, there’s a huge amount of waste, limited value activity, agonising project management by the client5 (if they are able)…and very little evidence of (true) Case Management.

Many a service manager may respond with “Yes, I get the downsides…but given the huge volume of cases that we are dealing with…what choice do I have?”

And so to discuss this…

The situation:

- Demand: There will be varying levels of complexity6 to clients at the point that they enter the system (or perhaps at a later point, when a ‘case manager’ first becomes valuable to them7)

- Supply: There will be varying levels of capability of staff members in terms of what they’ve seen/experienced/ learned to date.

i.e. each client (& their needs) will be unique, as will be each staff member (& their capability).

- Matching: There is a need to effectively match an appropriate staff member to a client at the point when a case manager first becomes valuable.

…and you may now be thinking ‘hang on…that means the answer is tiered services!’

But no, I’ve merely set out the situation, not the response to it.

Three (linked) concepts to introduce before going further:

- The Flow channel;

- Experiential learning; and

- Pulling for support

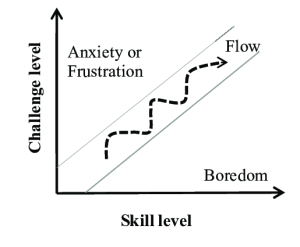

1. The flow channel: The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi spent his life researching the subject of ‘flow’ (the optimal experience for a human, where they become fully immersed in an activity. Ref. being ‘in the zone’)8

“The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile….”

“The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile….”

The diagram illustrates that Flow is achieved when there is a healthy correlation between the skill of the person and the challenge of the task.

Too easy and we get boredom, too hard and we get anxiety and frustration.

If we ‘do the same things’ all the time, then we will increase our skill at doing these things…and become bored.

The opposite of this is being ‘thrown in at the deep end’ (i.e. set a challenge way above our current skill level) …which is not a good place for anyone to be!

The flow channel is the dynamic sweet spot where our skills develop over time along with the level of challenges in front of us.

In short: if an organisation desires its labour force to really engage with their work (for the good of the client), then they ought to design the work such that everyone is constantly ‘moving up’ within their personal flow channel. Conversely, assigning workers into standardised tiers will lead to boredom within a tier and then anxiety as and when someone gets promoted (jumps) into a ‘higher’ (unfamiliar) tier.

Which leads nicely on to…

2. Experiential learning: The best way to learn is ‘live – with a real one’.

Many organisations subject their staff to multi-week classroom/online courses in which they are trained using made-up scenarios that supposedly cover off the variety of demands that will present on them when they are back ‘in the work’. There’s lots of issues with this method of (attempted) capability development such as:

- Each classroom scenario is contrived: it’s been made up, to work as intended;

- Role play: it doesn’t replicate how people will really behave – including the variety and uncertainty inherent within this;

- The training scenarios can only cover a fraction of reality – there’s loads more variety out there;

- Back in the work: Trainees see each instance of reality and attempt to fit it to one of the scenarios they were trained in;

- Time delay: Even if a training scenario is relevant, it’s a lottery as to if/when the trainee gets to handle a real one of that type. It could be, say, 6 months after the course…and then all is forgotten (#startfromscratch).

Far better would be to educate people on the basic principles and then supervise them ‘dealing with the real thing’ – the learning curve will be rapid.

Note: the supervision is important so that we don’t fall foul of the anxiety side of the flow channel.

Which leads nicely on to…

3. Pulling for support: Supervision at the start, then always available ‘live’ thereafter.

The idea of ‘pulling for support’ is the service version of the manufacturing ‘stop the line’.

If someone doing the work meets an obstacle in helping their client (and this can be as simple as ‘I think I know what to do…but I’m not sure’), then the service is designed such that they ‘pull the cord’ to gain help ‘there and then’ from people with the capability to assist. This would be the opposite of passing the problem off elsewhere (either back to the client or on to another team – #referral).

Note: Of huge importance is that this pulling for support is (truly) desired – evidently appreciated – by those in management….so that the worker wants to use it.

- Every pull ensures that a client gets a better service (towards purpose);

- Every pull increases the capability of a worker (and moves them up their personal flow channel);

- Every pull informs management about their system (where the obstacles are, where to focus) and about their people (where they are on their development journey, what challenges to work on next)

Putting things together: Some principles for service design

Understanding enough:

- We should design up-front interaction(s) such that a good understanding is gained of the nature of the client and their complexity. This won’t be perfect knowledge (because it can’t be)…but enough use to match them to the set of case managers who are usefully able to help.

Who takes (pulls) what cases?

- We don’t give client cases to staff members who would be way out of their depth in dealing with them…BUT neither do we need a staff member with the ‘perfect’ expertise for the case in question (ref. risk of boredom)

- There will be a large range of staff members who could ‘take on a case’, where the difference will be whether they need supervision and/or how much pulling for support will occur.

- We should want cases to go to people who can use them to grow their capability (ref. experiential learning).

- Given this, the best person to ‘take on the case’ is most likely the person who performed the ‘up-front’ interaction!

Note: You might be thinking that, if we ‘remove’ the tiers, then there will be chaos with hundreds, even thousands of case managers ‘floating around’. This doesn’t have to be the case. An alternative to experiment with would be (what we might refer to as) ‘pods’ of workers – sensibly sized self-managed teams* of case managers – with a mixture of capabilities, able to support and develop each other.

* for reference, the well regarded Dutch healthcare organisation Buurtzorg has settled on 12 members being their optimum team size…although I’m not advocating others merely copy them! Your pod size may very well be different…and perhaps vary by, say, location.

What happens when the nature of a case changes?

- We should (attempt to9) keep continuity between client and their case manager throughout the client’s dynamic journey.

- Things will change. Imagine two extreme scenarios:

- something that looked straightforward turned out to be complex; and

- something that was complex has progressed to now being straight forward.

- This first scenario is a fantastic capability development opportunity for the case manager. They already have a relationship with the client, they’ve understood that things have changed and why, and they are brilliantly placed to ‘learn live’, with support. It will be ‘capability development’ on steroids – no need to wait for that ‘next level’ training course scheduled for 12 months’ time!

- The second scenario is a great opportunity for a highly experienced case manager to effectively finish the case that they’ve owned (and not let it ‘get away again’ if it were handed on to somewhere else). They also get some respite from a tough portfolio of cases…ready to take on the next challenge.

- The above will provide each case manager with a mix of cases, which should provide interesting and varied work. Such a mix will provide ever-changing never-ending instances of challenge that consistently develops them (ref. personal flow channel)

Management Implications:

- Management don’t assign a worker to a static ‘service tier’ capability level, with them only working on these types of cases (and passing them elsewhere as and when things change or turn out to be different than expected)

- Management do maintain a good understanding of the ever-increasing capabilities of all their workers, with this showing them who can be matched to what, with what level of support.

- The focus is first on effectiveness…which will lead to efficiency, because all that wasted ‘passing it around and around, re-doing, and undoing’ work can be removed.

A very brief summary:

Continuity of service (i.e. someone that takes responsibility) = best for client.

Continual capability development = best for the organisation/ system.

Intrinsic motivation (ref. Flow channel) = best for the employee.

Effectiveness, leading to efficiency = best for everyone (including whoever funds the system)

And finally: This has been a long, involved post. I deliberately introduced it as being “some opening thoughts” rather than it being a complete ‘all tied up with a ribbon’ solution. The subject could easily be written into a book (or three). My purpose in writing the above is to say that:

- it is extremely worthwhile experimenting with a better way than the conventional ‘tiered service model’; and

- there’s a good set of principles from which to base such experimentation on.

…and if you read all the way to here, thanks…I hope it was worth it 🙂

Footnotes

1. Aspects of your life: such as unemployment; a problematic personal relationship; or health-related issues… or – as is usually the case – an entanglement of many such scenarios

2. Origin of ‘Case Manager’: Various articles refer to mid/late 1800s and early 1900s in the medical field (particularly psychiatry, social work and nursing in a community setting).

3. Client: or whatever name is most appropriate for the system within the frame of interest (e.g. patient,….)

4. Re. trust, and the ‘first date’ analogy: If you were to go on a first date, you are likely to be careful about the information you divulge. If you then go on a 2nd date, you might be more open….and after a few months of bliss you might be telling them ‘the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth’.

The point: On that first interaction, even if everything about the person ‘sat opposite you’ might look perfect…you are going to be careful…until you have gained suitable feedback that makes you feel safe.

5. Client Project Management: I regularly experience feelings of outrage when observing service designs that a) ought to be helping incredibly vulnerable people with complex needs and yet b) necessitate these same people to have to ‘project manage’ themselves through the service…because they are being passed from ‘pillar to post’ and/or languishing in no-man’s land!

6. Client complexity: ref. all the dimensions of their problematic situation and therefore the needs arising.

7. When a Case Manager becomes valuable: This post isn’t denying that many of us (me included) really value the ability to ‘self-serve’ numerous things online (i.e. do the basics without having to deal with a human). BUT – and this is a big but – there is regularly a point when the desire to self-serve ends, and we move into needing (what I might term) real help.

8. Flow: theflowchannelfoundation.org

9.Attempt to keep continuity: This won’t always be possible due to things like…

- the staff member becomes unavailable (e.g. sickness, retires/ leaves role); or

- the ‘client – staff member’ relationship has not been able to work (which can sometimes happen)

10. On ‘Case Management’ Philosophy and Guiding Principles: Some important aspects pulled out of Introduction to the Case Management Body of Knowledge | CCMC’s Case Management Body of Knowledge (CMBOK) (cmbodyofknowledge.com)

The primary function of Case Managers is to advocate for clients.

Other functions include:

-

- Communication

- Collaboration

- Education

- Identification of service resources [i.e. potential assistance], and then

- Facilitation/co-ordination of service [i.e. of assistance]

Case Managers aim to achieve quality outcomes for their clients.

-

- their first duty is to their clients.

Case Management should be:

-

- holistic: understanding, and handling, the fuller client situation

- adaptive: to each client, and over the course of time with a client

Case Management is guided by the principles of:

-

- Autonomy [Client self-determination]

- Beneficence [of benefit to the client]

- Non-maleficence [Do no harm…noting that failing to act may do harm]; and

- Justice [Fairness]

11. The image is of a multi-tiered cake that has gone awry.