Are you interested in crossing that divide?

Are you interested in crossing that divide?

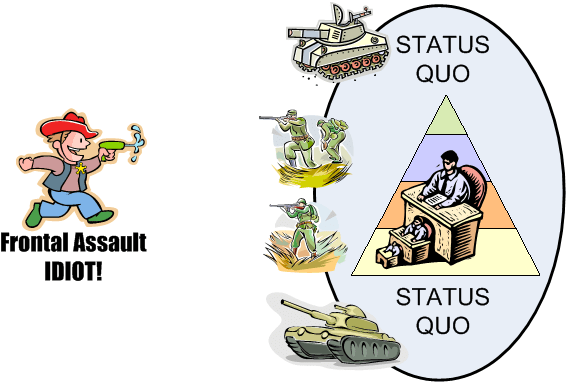

Okay, listen up 🙂 …this post is my attempt at one of those important bringing-it-all-together ones that provide a big message (see – look at the picture!)…which means that it’s a bit longer than normal because it needs to be.

I thought about breaking it into pieces and publishing bit-by-bit but this would make it longer (each bit needing a top and a tail) and hard to mentally put back together.

So I’ve decided to keep it together and let you, the reader, decide how you consume it. You might like to read it in one; or dip in and out of it during your day; or even set yourself an alert to finish it the next day…so (as Cilla Black used to say) “the choice is yours”. Here goes…

Mike Rother wrote what I believe to be, a very important book (Toyota Kata) about how organisations can improve, and what thinking is stopping them.

In particular, Chapter 9 of the book deals with ‘Developing Improvement Kata [pattern] behaviour in your organisation’. I thought it worthwhile posting a summary of his excellent advice derived from his research….

…and I’ll start with a highly relevant quote:

“Do not create a ‘Lean’ department or group and relegate responsibility for developing improvement behaviours to it.

Such a parallel staff group will be powerless to effect change, and this approach has been proven ineffective in abundance.

Use of this tactic often indicates delegation of responsibility and lack of commitment at the senior level.” (Mike Rother)

Many an organisation has gone down the ‘Lean department’ (or some such label) route…so, given this fact, here’s what Rother goes on to say, combined with my own supporting narrative and thought:

1. Be clear on what we are trying to achieve

If you really want to cross that divide then the challenge that we should be setting ourselves is learning a new way of thinking and acting such that we:

- get the ‘improvement behaviour’ habit into the organisation; and then

- spread it across the organisation so that it is used by everyone, at every process, every day.

And to make it even more ‘black and white’: the challenge is NOT about implementing techniques, practices or principles on top of our existing way of managing.

It means changing how we manage. This involves a significant effort and far reaching change (particularly in respect of leadership).

2. What do we know about this challenge?

- Toyota (from the foundational work of Taiichi Ohno) is considered the world leader in working towards this challenge…they’ve been working towards it for 60+ years;

- We can study and learn, but should not merely copy, from them;

- The start, and ever-continuing path, is to strive to understand the reality of your own situation, and experimenting. This is where we actually learn;

- No one can provide you with an ‘off-the-shelf’ solution to the challenge:

- There isn’t likely to be an approach that perfectly fits for all;

- It is in the studying and experimenting that we gain wisdom;

- ‘Copying’ will leave us flailing around, unknowingly blind;

- Our path should continually be uncertain up until each ‘next step’ reveals itself to us.

Wow, so that’s quite a challenge then! Here are some words of encouragement from Rother on this:

“There is now a growing community of organisations that are working on this, whose senior leaders recognise that Toyota’s approach is more about working to change people’s behaviour patterns than about implementing techniques, practises, or principles.”

3. What won’t work?

If we wish to spread a new (improvement) behaviour pattern across an organisation then the following tactics will not be effective:

Tactic a) Classroom training:

Classroom training (even if it incorporates exercises and simulations) will not change people’s behaviours. If a person ‘goes back’ into their role after attending training and their environment remains the same, then expect minimal change from them.

“Intellectual knowledge alone generally does not lead to change in behaviour, habits or culture. Ask any smoker.”

Rother makes the useful contrast of the use of the ‘training’ word within sport:

“The concept of training in sports is quite different from what ‘training’ has come to mean in our companies. In sport it means repeatedly practicing an actual activity under the guidance of a coach. That kind of training, if applied as part of an overall strategy to develop new behaviour patterns is effective for changing behaviours.”

Classroom training (and, even better, education) has a role but this is probably limited to ‘awareness’….and even that tends to fade quickly if it is not soon followed by hands-on practising with an appropriate coach.

Tactic b) Having consultants do it ‘to people’ via projects and workshops:

Projects and workshops do not equal continuous improvement. This is merely ‘point’ improvement that will likely cease and even slip backwards once the consultant (or ‘Black Belt’) has moved on to the next area of focus.

Real continuous improvement means improving all processes every day.

Traditional thinking sees improvement as an add-on (via the likes of Lean Six Sigma projects) to daily management. Toyota/ (actual) Lean/ Systems thinking (pick your label!) is where normal daily management equals process improvement i.e. they are one and the same thing.

To achieve this isn’t about bringing experts in to manage you through projects; it is to understand how to change your management system so that people are constantly improving their processes themselves. Sure, competent coaches can help leaders through this, but they cannot ‘do it for them.’

And to be clear: it is the senior leaders that first need coaching, this can’t be delegated downwards.

“If the top does not change behaviour and lead, then the organisation will not change either.”

Tactic c) Setting objectives, metrics and incentives to bring about the desired change:

There is no combination of these things that will generate improvement behaviour and alter an organisation’s culture. In fact, much of this is the problem.

If you don’t get this HUGE constraint then here are a few posts already published that scratch the surface* as to why: D.U.M.B., The Spice of Life, and The Chasm

(* you are unlikely to fully ‘get’ the significance from simple rational explanations, but these might make you curious to explore further)

Tactic d) Reorganising:

Shuffling the organisational structure with the aim (hope) of stimulating improvement will not work. Nothing has fundamentally changed.

“As tempting as it sometimes seems, you cannot reorganise your way to continuous improvement and adaptiveness. What is decisive is not the form of your organisation, but how people act and react.”

4. How do we change?

So, if all those things don’t work then, before we jump on some other ideas, perhaps we need to remind ourselves about us (human beings) and how we function.

The science of psychology is clear that we learn habits (i.e. behaviours that occur unconsciously and become almost involuntary to us) by repeated practice and gaining periodic fulfilment from this. This builds new and ever strengthening mental circuits (neural pathways).

Put simply: we learn by doing.

We need to start by realising that what we do now is mostly habitual and therefore the only way to alter this is by personally and repeatedly practising the desired (improvement pattern) behaviours in our actual daily work.

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” (Aristotle)

“To know and not to do is not yet to know.” (Zen saying)

Further, a coach can only properly understand a person’s true thinking and learning by observing them in their daily work.

In summary, we need to:

- practise using actual situations in actual work processes;

- combine training with doing, such that the coach can see in real time where the learner is at and can introduce appropriate adjustments; and

- use the capability of the actual process as the measure of effectiveness of the coaching/ learning.

5. Where to start?

So, bearing in mind what is said above (i.e. about needing to learn for yourselves), what follows is merely about helping you do this…and not any ‘holy grail’. If there is one then it is still up to you to find it!

An experienced coach:

“Coaches should be in a position to evaluate what their students are doing and give good advice…in other words, coaches should be experienced….

…If a coach or leader does not know from personal experience how to grasp the current condition at a process, establish an appropriate challenge [towards customer purpose] and then work step by step [experiment] towards it, then she is simply not in a position to lead and teach others. All she will be able to say in response to a student’s proposals is ‘Okay’ or ‘Good job’ which is not coaching or teaching.

The catch-22 is that at the outset there are not enough people in the organisation who have enough experience with the improvement kata [pattern] to function as coaches…

…it will be imperative to develop at least a few coaches as early as possible.” (See establishing an Advance Group below)

A word of warning: Many people assume a coaching role, often without realising that they are doing so. Such a presumption seems to be something that anyone hierarchically ‘senior’ to you considers to be their right. As in “Now listen up minion, I am now going to coach you – you lucky thing!*”

(* I had a rant about this in my earlier post on ‘people and relationships’ …but I’m okay now 🙂 )

So: Before any of us assert any supposed coaching privileges, I think we should humbly reflect that:

“The beginner is entitled to a master for a teacher. A hack can do incredible damage.” (Deming)

Who practises first?

The improvement pattern is for everyone in the organisation……but it needs to start somewhere first.

“Managers and leaders at the middle and lower levels of the organisation are the people who will ultimately coach the change to the improvement kata [pattern], yet they will generally and understandably not set out in such a new direction on their own. They will wait and see, based on the actions (not the words) of senior management, what truly is the priority and what really is going to happen.”

The point being that, if the organisation wants to effect a change in culture (which is what is actually needed to make improvement part of daily management) then it requires the senior managers to go first.

This statement needs some important clarifications:

- It isn’t saying that senior leadership need to stand up at annual road-shows or hand out some new guru-book and merely state that they are now adopting some shiny new thing. This will change nothing. Far better would be NOT to shout about it and just ‘do it’ (the changed behaviours)…the people will notice and follow for themselves;

- It isn’t saying that all senior leaders need to master all there is to know before anyone else can become involved. But what is needed is a meaningful desire for key (influential) members of the senior team to want to learn and change such that their people believe this;

- It isn’t saying that there aren’t and won’t be a rump of middle and lower managers who are forward thinking active participants. They exist now and are already struggling against the current – they will surge ahead when leaders turn the tide;

- It isn’t saying that the rest of the people won’t want the change: the underlying improvement behaviours provide people with what they want (a safe, secure and stimulating environment). It is just that they have understandably adopted a ‘wait-and-see’ habit given their current position on a hierarchical ladder and the controls imposed upon them.

Establishing an Advance Group

The first thing to notice from this sub-title is that it is NOT suggesting that:

- we should attempt to change the whole organisation at once; or that

- we should set up some central specialist group (as in the first quote in this post)

Instead, it is suggesting that we:

- find a suitable1 senior executive to lead (not merely sponsor!2);

- select/ appoint an experienced coach;

- select a specific value-adding business system3 to start with;

- form a suitable1 group of managers (currently working in the system, not outside it);

- provide initial ‘awareness’ education;

- ‘go to the Gemba’ and study4 to:

- gain knowledge about purpose, demand, capability, and flow; and then

- derive wisdom about the system conditions and management thinking that make all this so;

- perform a series of improvement cycles (experimenting and learning);

- reflect on learnings about our processes, our people and our organisation…

- …deriving feelings of success and leading to a new mindset: building a capability to habitually follow the improvement routine in their daily management;

- …and thereby crafting a group of newly experienced managers within the organisation who can go on to coach others as and when other business systems wish to pull their help.

(for explanatory notes for superscripts 1 – 4, see bottom of post)

Caution: Don’t put a timescale on the above – it can’t be put into an ‘on time/budget/scope’ project straight jacket. The combination of business system, team and organisational environment is infinitely varied…it will take what it takes for them to perform and learn. The learning will emerge.

A number of things should be achieved from this:

- meaningful understanding and improvement of the selected business system’s capability;

- highly engaged people who feel valued, involved and newly fulfilled;

- a desire to continue with, and mature the improvement cycles (i.e. a recognition that it is a never-ending journey);

- interest from elsewhere in the organisation as they become aware of, develop curiosity and go see for themselves; and

- A desire to ‘roll in’5 the change to their own business system.

A caveat – The big barrier:

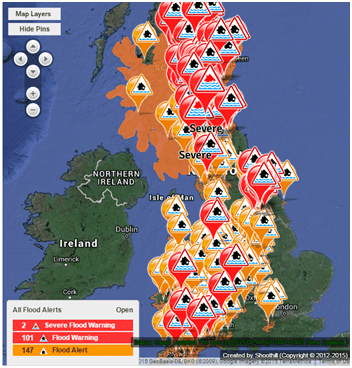

Every system sits within (and therefore is a component of) a larger system! This will affect what can be done.

If you select a specific value-adding business system, it sits within the larger organisational system;

If you move up the ‘food chain’ to the organisational system, it potentially sits within a larger ‘parent organisation’ system

….and so on.

This is a fact of life. When studying a system it is as important (and often more so) to study the bigger system that it sits within as studying its own component parts.

It is this fact “that so often brings an expression similar to that of the Sheriff Brody in the film ‘Jaws’ when he turns from the shark and says ‘we need a bigger boat’. Indeed we do!” (Gordon Housworth, ICG blog)

If the bigger system commands down to yours (such as that you must use cascaded personal objectives, targets, contingent rewards and competitive awards) and your learning (through study and experimentation) concludes that this negatively affects your chosen business system then you need to move upstairs and work on that bigger system.

You might respond “But how can we move upstairs? They don’t want to change!”. Well, through your studying and experimentation, you now have real knowledge rather than opinions – you have a far better starting point!

…and there you have it: A summary of Mike Rother’s excellent chapter mixed with John Seddon’s thinking (along with my additional narrative) on how we might move towards a true ‘culture of improvement’.

There is no silver bullet, just good people studying their system and facilitating valuable interventions.

Notes: All quotes used above are from Mike Rother unless otherwise stated.

- Suitable: A person with: an open mind, a willingness to question assumptions/ conventional wisdom, and humility; a desire and aptitude for self-development, development of others and for continual improvement (derived from Liker’s book – The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership)

- On leading: “Being a…Sponsor is like being the Queen: you turn up to launch a ship, smash the champagne, wave goodbye and welcome it back to port six months later. This attitude is totally inappropriate for leading…in our business environment. We need ownership that is one of passion and continual involvement…” (Eddie Obeng)

- The business system selected needs to be a horizontal value stream (for the customer) rather than a vertical silo (organisational function) and needs to be within the remit of the senior executive.

- Study: Where my post is referring to Seddon’s ‘Check’ model

- Roll in: The opposite of roll out – pulling, instead of pushing. Please see Rolling, rolling, rolling… for an explanation of the difference.

Are you interested in crossing that divide?

Are you interested in crossing that divide? A TV program of old that is a huge favourite of mine is the 1980s British comedy ‘Blackadder’.

A TV program of old that is a huge favourite of mine is the 1980s British comedy ‘Blackadder’.

So I moved house a few months ago and I’ve been really slow at updating my address details with all those organisations that have wheedled their way into my life – I am suffering from the well known condition called ‘Post Office redirection service’ apathy.

So I moved house a few months ago and I’ve been really slow at updating my address details with all those organisations that have wheedled their way into my life – I am suffering from the well known condition called ‘Post Office redirection service’ apathy.