I’ve been meaning to write a post about promotion (into, and through the hierarchy of management) for a while now…it’s taken me a bit to frame it. Here’s ‘part 1’:

I’ve been meaning to write a post about promotion (into, and through the hierarchy of management) for a while now…it’s taken me a bit to frame it. Here’s ‘part 1’:

Before considering promotion we should ask ourselves…

What is the work of management?

A great deal has been written on this question. Womack’s essay ‘The work of management’ gives us an all too familiar view as to what management actually means in practice:

“Most managers I observe spend most of their time with incidental work – box ticking, meetings that reach no actionable conclusions, report writing, personnel reviews that don’t develop personnel, etc. And in the time left over they do rework. By the latter I mean the fire fighting to get things back on course as processes malfunction. Most managers seem to believe that this is their ‘real’ work and their highest value to their organisation.”

Is this what we actually want our managers to be doing? Does this create value or is it just about survival?

Who do we hire/ promote into management?

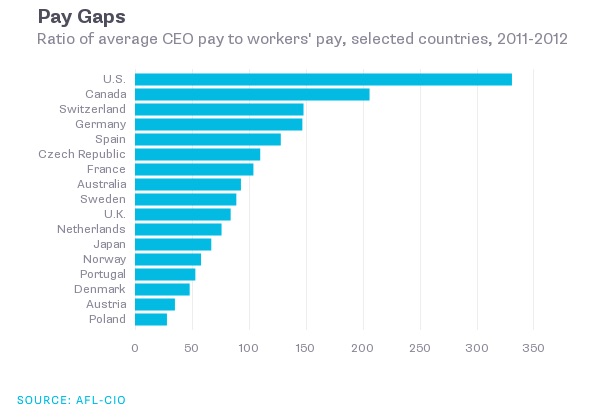

In another of his essays, ‘Fewer Heroes, More Farmers’, Womack explains that when he asked a Command & Control CEO at a very large American Corporation about his management hiring/ promotion logic he got the following in reply: “I search for heroic leaders to galvanize my business units. I give them metrics to meet quickly. When they meet them they are richly rewarded. When they don’t, I find new leaders.”

Womack went on to ask this CEO, given the very high level of turnover of his business unit heads, “why does your company need so many heroes? Why don’t your businesses consistently perform at a high level so that no new leaders are needed? And why do even your apparently successful leaders keep moving on?”

He got the usual answers in reply: “business is tough, leadership is the critical scarce resource, and that a lot of turnover indicates a dynamic management culture.”

…and yet such businesses preside over:

- A confusion as to its purpose (a mismatch between what is stated and reality);

- The constant rolling out of the latest ‘revitalising’ programme from the top;

- Poorly performing processes, that tend to get worse instead of better;

- Dispirited people operating these broken processes at every level of the organisation; with

- Mini-heroes everywhere devising workarounds.

Rather than heroes, Womack suggests that we need farmers whose role is to steadily tend every important process, continually asking three simple questions:

- Is the business purpose of the process [in the eyes of the customer] correctly defined? [and Seddon would add ‘is its capability measured?’]

- Is action steadily being taken to create value, flow and pull in every step of the process while taking out waste?

- Are all of the people touching the process actively engaged in making it better?

“This is the gemba mentality of the farmer who, year after year, plows a straight furrow, mends the fence and obsesses about the weather, even as the heroic pioneer or hunter who originally cleared the land moves on.

Why do we have so many heroes and so few farmers, and such poor results in most of our organisations? Because we’re blind to the simple fact that business heroes usually fail to transform businesses. They create short-term improvement, at least on the official metrics. But these gains either aren’t real or they can’t be sustained because no farmers are put in place to tend the fields. Wisely, these heroes move on before this becomes apparent.

Meanwhile, we are equally blind to the critical contribution of the farmers who should be our heroes. These are the folks who provide the steady-paced continuity at the core of every lean enterprise”.

Now, after reading the above back to myself, I can feel a back lash from the current cool management buzz of ‘everything today is about innovation!’…as in “but the world is ever changing Steve! We can’t just rely on Continuous Improvement – we’ve got to constantly reinvent ourselves or else we will get left behind!”

I agree! What is written above isn’t confined to making small step changes and doesn’t constrain discontinuous (breakthrough) improvements. Womack’s 3 questions equally apply for the seeds of innovation to blossom within a healthy working environment.

Conversely, hero management with financial targets and contingent rewards can seriously damage the chances of true and meaningful innovation from happening. (Both Alfie Kohn and Dan Pink explain the research showing the harm that incentives do to innovation).

If your purpose is clear and everyone is working together towards it (not towards individual targets) then you will likely alternate between many small steps and infrequent leaps as new ideas and technologies come along and existing ones are steadily improved.

Who should we want as our managers?

“The greatness in people comes out only when they are led by great leaders” (Akio Toyoda)

Liker, in his excellent book ‘The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership’, explains Toyota’s leadership development model. He explains it in four building blocks:

(Note: whilst I am mixing the words ‘leader’ and ‘manager’, there is a big difference between them. Please reflect on Confusion over two words)

First, to be considered for leadership, a person has to be committed to self-development i.e. to constantly seek to improve themselves and their skills. This is enabled and assessed by those ahead1 of them providing suitable challenges, space and coaching to allow self-development to occur.

Clarification: You may have years of experience and/or rolls of qualifications…but this doesn’t demonstrate that you have, or can, self-develop:

“What is often mistaken for 20 years’ experience is just 1 year’s experience repeated 20 times” (Source unknown)

Not everyone will be up for self-development2. Clearly, Toyota are looking for those who can and want to grow. This is in stark contrast to organisations that want merely to bring in people from outside to ‘implement here what they have done to people elsewhere’ (but now appear to be running away from this!)

Second: Once a person has suitably demonstrated their ability and desire to self develop, then they need to show the development of others. To be clear: this does not mean merely coaching (supposedly) star performers or favourites (the ‘chosen few’)…it means developing everyone. In fact, your ability to develop someone where this appears challenging* is a sure sign of your development capabilities. Liker uses the Toyota quote that “the best measure of a leader’s success is what is accomplished by those they trained3.” It’s not about what you can do; it’s about what they can now do because of you (even though they may not comprehend this link).

(*The greatest case study I know of this is what Toyota achieved at NUMMI with ex-GM employees who were considered the worst of the worst. They re-hired them and turned them into the best. The problem wasn’t a shortage of talent, as we are so often led to believe, but an inability to engage and develop the talents lying dormant within people).

Third: So you are a self-developer and can develop others. It now becomes about your ability to enable daily improvement – facilitating groups of people through constant improvement: being a farmer as described above.

The focus is not on attempting to force improvement (top down) but in enabling, encouraging and coaching improvement from the bottom up.

Clarification: This is NOT about that ’empowerment’ word!

…and, finally, Fourth: It is now about ensuring that the right big-picture challenges are set, pursued and accomplished by the people and, in so doing, that this causes much experimentation, reflection and learning.

None of this leadership development logic is about being promoted because you are the best at performing your current job or that you are a hardened ‘go get ’em’ management hero. All of it is about your ability to facilitate improvement through others.

Managers instead of Consultants

…this leads me to observe that many a ‘command and control’ manager brings in consultants (or ‘Black Belts’) to facilitate his/her team through the likes of a Kaizen/ Rapid Improvement Event.

- Worse still, such facilitators often prefer that the manager isn’t involved in these improvement events (except as ‘statesman’ at the beginning and ‘rubber stamper’ at the end) because their presence would seriously hinder what the people can achieve.

- To add insult to injury, such an absent manager has attempted to delegate their improvement responsibilities and thus finds themselves even further from the work (the gemba) and with new/ higher barriers between themselves and their people.

…owch! If this is the case (and, sadly, it often is) then this is a very poor state to be in.

At Toyota, facilitation of improvement is what their managers are for! And, rather than a week-long ‘point improvement’ event performed every (say) 6 months, this facilitation should be ongoing.

You might respond that “Nice idea Steve…but our managers don’t have very good facilitation skills. We need expert practitioners to come in”. And that is precisely why Toyota looks for those people within its ranks that have the potential as facilitators of improvement…and then develops them into leaders.

Rother makes clear that “The primary task of Toyota’s managers and leaders does not revolve around improvement per se, but around increasing the improvement capability of people. That capability is what, in Toyota’s view, strengthens the company. Toyota’s managers and leaders develop people who in turn improve processes through the improvement kata [pattern].

Developing the improvement capability of people at Toyota is not relegated to the human resources or the training and development departments. It is part of every day’s work in every area…”

Sense-check: It may be that your current managers are (or could be) great facilitators. However, if they have to use a ‘command and control’ management system on their people then it is unlikely that such fantastic skills will get a chance to blossom and deliver the potential value within. Worse, their efforts will likely clash with all that commanding and controlling going on.

Next time you feel the need to bring in facilitators, reflect on why. Is it because your managers:

- don’t have the capability? or

- do have the potential, but are constrained by the management system that they are required to operate within?

If your answer is a), then develop them. If it’s b), you have far bigger fish to fry…but don’t let this stop you from doing anything – remember the Two Parallel Tracks.

______________________________________________________________________

To close:

- this post (Part 1) considers who we should be promoting, and why;

- Part 2 will turn this all on its head and question the promotion career ladder logic. In short: we can’t all ‘get to the top’ and neither should we all want to.

Notes:

- Ahead: I use the word ‘ahead’ rather than ‘above because I’d like the reader to get out of a ‘superiors in the hierarchy’ mindset and, instead, think about people who happen to have been promoted to more senior positions because they are more advanced on this leadership development journey. This is merely a matter of timing, rather than importance.

- Fixed vs. Growth mindset: Professor Carol Dweck’s research suggests that we can judge how good people will be at learning new skills – our capacity to learn is determined by our beliefs as to whether our abilities are innate or can be learned. Dweck suggests a continuum with two extremes: A Fixed mindset and a Growth mindset. Don’t despair of those already in leadership positions that appear to have ‘fixed’ mindsets. This may very well be down to the environment in which they work (and have always worked) within. The important bit is to assess them once their environment is changed to encourage self-development and growth.

- Trained: the use of the ‘trained’ word in this quote applies to its meaning as is used in sport. Rother notes that “The concept of training in sports is quite different from what ‘training’ has come to mean in our companies. In sport it means repeatedly practicing an actual activity under the guidance of a coach. That kind of training, if applied as part of an overall strategy to develop new behaviour patterns is effective for changing behaviours.”