Readers of this blog will have likely come across a phrase that I often use but which you might not be too clear on what is meant – this phrase is Capability Measure.

Readers of this blog will have likely come across a phrase that I often use but which you might not be too clear on what is meant – this phrase is Capability Measure.

(Note: I first came across the use of this specific phrase from reading the mind opening work of John Seddon).

I thought it worthwhile to devote a post to expand upon these two words and, hopefully, make them very clear.

Now, there are loads of words bandied around when it comes to the use of numbers: measures, metrics, KPIs, targets. Are they all the same or are they in fact different?

Let’s use the good old Oxford dictionary to gain some insights that might assist:

Measure: “An indication of the degree, extent, or quality of something”

Metric: “A system or standard of measurement”

KPI (Key performance indicator): “A quantifiable measure used to evaluate the success of an organization, employee, etc. in meeting objectives for performance.”

Target: “An objective or result towards which efforts are directed”

So putting these together:

A measure quantifies something…but this of itself doesn’t make it useful. It depends on what you are measuring! In fact, there is a huge risk that something that is easily measureable unduly influences us:

“We tend to overvalue the things we can measure and undervalue the things we cannot.” (John Hayes)

A metric is the way that a measurement is performed – it’s operational definition. There’s not much point in taking two measurements of something if the method of doing so differs so much as to materially affect the results obtained.

KPIs are an attempt to get away from using lots of different measures and, instead, boil them down into a handful of (supposedly) ‘important ones’ because then that will make it sooo much easier to manage won’t it?…I hope your ‘Systems thinking’ alarm bells are ringing – if we want to understand what is really happening, we need to study the system. Any attempts at short-cutting this understanding, combined with the use of targets and extrinsic motivators is likely to lead to some highly dysfunctional behaviour, causing much damage and resulting in sub-optimal outcomes. The idea of ‘management by dashboard’ is deeply flawed.

Targets – well, where to start! The dictionary definition clearly shows that their use is an attempt at ‘managing by results’…which is a daft way to manage! We don’t need a target to measure…and we don’t need (and shouldn’t attempt) to use a target to improve! A target tells us nothing about the system; distorts our thinking; and steals our focus from where it should be.

So what are we measuring?

I hope I’ve usefully covered ‘measure’ and its related terms so let’s go back to the first word: Capability

To start, we need to be clear as to what system we are studying and what its purpose is from the customer’s point of view. Then we need to ask ourselves “so what would show us how capable we are of meeting this purpose (in customer terms)?”

Some important points:

- Capability is always about meeting the customer’s purpose and should be separate from the method of doing so:

- An activity measure (i.e. to do with method), such as “how many calls did I take today”, is NOT a capability measure. None of my customers care how many calls I took/made!;

- Activity measures constrain method (tie us in to the current way of working i.e. “we make calls”) whilst capability measures liberate method and encourage experimentation (“what would happen to our capability if we…”).

- The best people to explain what really matters to the customer are the front line process performers who help them with their needs (i.e. NOT managers who are remote from the gemba):

- The process performers know what the customers actually want and whether they are satisfied or not

- As a rule of thumb, the end-to-end process time from the customer’s point of view is almost always an essential capability measure BUT:

- end-to-end is defined by the customer, not when we think we have finished;

- Targets will distort the data that we collect and thereby lead to incorrect findings…so, if you really want to understand your system’s capability you need to remove the targets and related contingent rewards.

- Other examples of likely capability measures of use are:

- A system’s ‘one-stop capability’: the amount of demand that can be fully satisfied (as determined by the customer) in one-stop;

- The accuracy and value created for the customer; and

- The safety and well-being of your people whilst delivering to the customer

An example:

I am currently moving house. I have to switch the electricity provision from the previous occupants to me. I want this switch to happen as painlessly as possible, I only want to pay for my electricity usage (none of theirs) and I want the confidence to believe that this is the case.

So:

- The system in question is the electricity switching process;

- My purpose is to switch:

- Easily (minimum effort on my part….easy to start the process, no need to chase up what is happening, and easy to know when it is complete)

- On time (on the switching date/ time requested); and

- Transparently (so that I trust the meter readings and their timings)

- I don’t care how the electricity companies actually achieve this switching between themselves (the method, such as whether they use a SMART meter reading or a man comes to the house or…). I just care about the outcomes for me.

The electricity company should be deriving measures to determine how capable they are in achieving against my purpose. They are then free to experiment on method and see whether their capability improves.

I have deliberately used a generic example to make the point about the system in question, its purpose and therefore capability. You can apply this thinking to your work: what the customer actually wants/ needs and how you would know how you are doing against this.

Sense-check: Capability measures are method-agnostic. Think about putting your method inside a metaphorical ‘black box’. Your capability is about what goes into the black box as compared to what comes out and what has been achieved. You can then do ‘magic’ (I mean experiments!) as to what’s inside the black box and then objectively consider whether its capability has improved or not.

What does a capability measure look like, who should see it and why?

Okay, so let’s suppose we now have some useful capability measures. How should they be presented and to whom…and what are we hoping to achieve by this?

The first big point is that the measure should be shown over time*. We should not be making binary comparisons, and then overlaying variance analysis and ‘traffic lights’ to supposedly add meaning to this (ref: Simon Guilfoyle’s excellent blog ).

We want to see the variation that is inherent in the system (the spice of life) so that we can truly see what is happening.

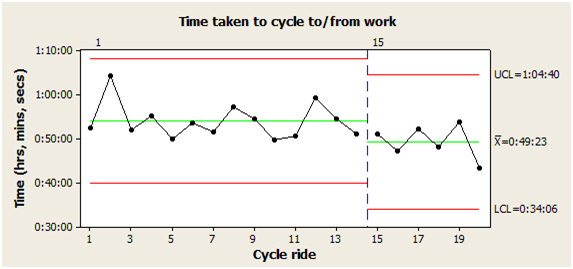

* Note: A control chart is the name for the type of graph used to study how a metric changes over time. The data is plotted in time order. Lines are added for the average, upper and lower control limits – where these are worked out from the data…but don’t worry about ‘how’ – these statistics can be worked out by an appropriate computer application (e.g. Minitab) in the hands of someone ‘in the know’.

Here’s a control chart showing the time it takes me to cycle to or from work:

The second big point is that these capability control charts should be in the hands of those who perform the work. There’s little point in them being hidden within some managerial report!

Here’s what Jeffrey Liker says about how Toyota use visual management:

Every metric that matters…is presented visually for everyone who is involved in meeting the goal [purpose] to see. A key reason…is that it clarifies expectations, determines accountability for all the parties involved and gives them the ability to track their progress and measure their self-development.

[Making these metrics highly visible] is not to control behaviour, as is common in many companies, but primarily to give employees a transparent and understandable way to measure their progress.

Put simply: if the people doing the work can see what is actually happening, they are then in a place to use their brains and think about why this is so, what they could experiment with and whether these changes improved things or not* ….and on and on.

* Looking back at my ‘cycling to work’ control chart: I made a change to my method at cycle ride number 15 and (with the caveat that I need more data to conclude) the control chart shows me whether my change in method made things better, worse or caused no improvement. I cannot tell this from a binary comparison with averages, up/down arrows and traffic lights.

It should by now be clear that a capability measure is about the system, and NOT about the supposed ‘performance’ of individual operators within.

To summarise:

In bringing the above together, John Seddon applies 3 tests to determine whether something is a good measure. These tests are:

- Does it relate to purpose? (i.e. what matters to the customer);

- Does it help in understanding and improving performance? (i.e. does it reveal how the work works? To do this, it must be a measure over time, showing the variation inherent within the system, and it must be devoid of targets);

- Is it integrated with the work? (i.e. in the hands of the people who do the work so that they can develop knowledge and hence improve).

If it passes these three tests then you truly have a useful Capability Measure!

As luck would have it: One of my favourite bloggers, ‘Think Purpose’, released a similar ‘measurement’ post just after I had written the above. It includes a couple of very useful pictures that should compliment my commentary. It’s called A managers guide to good and bad measures – you could print them out and put them on your wall 🙂

A clarification: I’m happy with the use of the word ‘target’ if it is combined with the word ‘condition’. A reminder that a target condition (per the work of Mike Rother) is a description of the desired future state (how a process should operate, intended normal pattern of operation). It is NOT a numeric activity target or deadline. I explain about this in my earlier post called…but why?