As part of the work that I do, my colleagues and I help people observe the systems that they manage and work within, to cause them to see important stuff which has ‘been hidden in plain sight’ and to think about what’s going on underneath, and why…with the aim of improvement.

As part of the work that I do, my colleagues and I help people observe the systems that they manage and work within, to cause them to see important stuff which has ‘been hidden in plain sight’ and to think about what’s going on underneath, and why…with the aim of improvement.

In doing this, we use a great deal of (what is often referred to as) reflective practice.

So, the other day I was asked1:

“What have you written on reflection that you can share with me?

…and I reflected that I haven’t specifically written anything on reflection 🙂

So, here goes2…

What is reflection?

The Oxford English dictionary defines reflection as “serious thought or consideration”.

Some key synonyms (in addition to thinking and consideration) are contemplation, study, deliberation, and pondering.

Underlying the desire (or need) to reflect is its role in achieving valuable learning.

“We do not learn from experience…we learn from reflecting on experience.” (John Dewey)

Dewey was clarifying that experience may be necessary, but it’s not sufficient. A good dose of reflection is required to make that experience valuable.

Levels of thoughtfulness

The following diagram (that I’ve fashioned from reading a paper by Jack Mezirow3) makes the point that we might categorise our thoughtfulness when performing actions:

The lowest level4, habit, is where something is done regularly, to the point at which we aren’t consciously thinking about it. We are likely to become relatively consistent (perhaps fixed), almost automatic about it.

One step up is thoughtful action. Here, we must use information to decide what direction(s) to take but, importantly, we are doing so without questioning ‘what we already know’:

It “takes place in action contexts in which implicitly raised theoretical and practical validity claims are naively taken for granted and accepted or rejected without discursive consideration.” (Habermas)

I think you’d agree with me that, if we are operating any work system just at the habit and thoughtful action levels, we can expect its performance to be, or become, ‘stuck’. Further, it’s likely to struggle with the unexpected.

And so, we get to reflection, which is broken into two levels:

Basic reflection is where we pause to consider what happened, or is happening, and what we think about this. Note that, to reflect, there is likely a need for the time and space to do so5.

Critical reflection is at a deeper level: It’s about ‘thinking about our thinking’. More on this below…

On critical reflection

I think that it’s become common for the word ‘critical’ to be put on the front of the word ‘reflection’ in conversations, as if merely saying this makes it so.

And it can be argued that reflection, by definition, is about critiquing something. But I think making the distinction between (basic) reflection and critical reflection is important. Here’s what Mezirow says on the subject:

“While all reflection implies an element of critique, the term ‘critical reflection’ will here be reserved to refer to challenging the validity of presuppositions in prior learning.” (Mezirow)

On reading this, I thought that it was saying something important, but I was unsure about the ‘presupposition’ word…so I looked it up:

Presupposition:

Simple definition: “something that you assume to be true, especially something that you must assume is true in order to continue with what you are saying or thinking.” (Collinsdictionary.com)

Deeper definition: “any supressed premise or background framework of thought necessary to make an argument valid, or a position tenable.” (Oxfordreference.com)

I find that these definitions help me.

We ‘do stuff’ without realising the foundations on which we assume them to be reasonable things to do…and if these foundations are limited, problematic, flawed, or even false, we are usually blind to this.

Examples:

- We break our organisations into specialised component parts, and pass stuff between them, assuming that this is a sensible thing to do

- We formulate fixed budgets, and ‘explain’ variance from them, assuming that this is a sensible thing to do

- We set arbitrary numerical targets, and report performance against them…assuming that this is a sensible thing to do

- We devise detailed rules and procedures, and check compliance with them… [you know what comes here]

- …I could go on

The assumptions in these examples are based on deeper ‘frameworks of thought’ which we are (typically) unaware of. Critical reflection would be to get down to this level – to ‘think about our thinking’.

Mezirow proposes that critical reflection might be viewed as:

“premise reflection – i.e. question[ing] the justification for the very premises on which problems are posed or defined in the first place.”

And so we get to (what I think is) quite a clean, working distinction between (basic) reflection and critical reflection:

“Critical reflection is not concerned with the ‘how’ of action, but with the ‘why’, the reasons for and the consequences of what we do.” (Mezirow)

I see a similarity between reflection vs. critical reflection, as described above, and single vs. double loop learning

(Basic) reflection might help us ‘do the wrong thing righter’ (ref. Ackoff)

Critical reflection might help us to move towards ‘doing the right things’.

A learning cycle

The above may be of interest, but you might now be wondering whether there are any models that could ‘help you get there’.

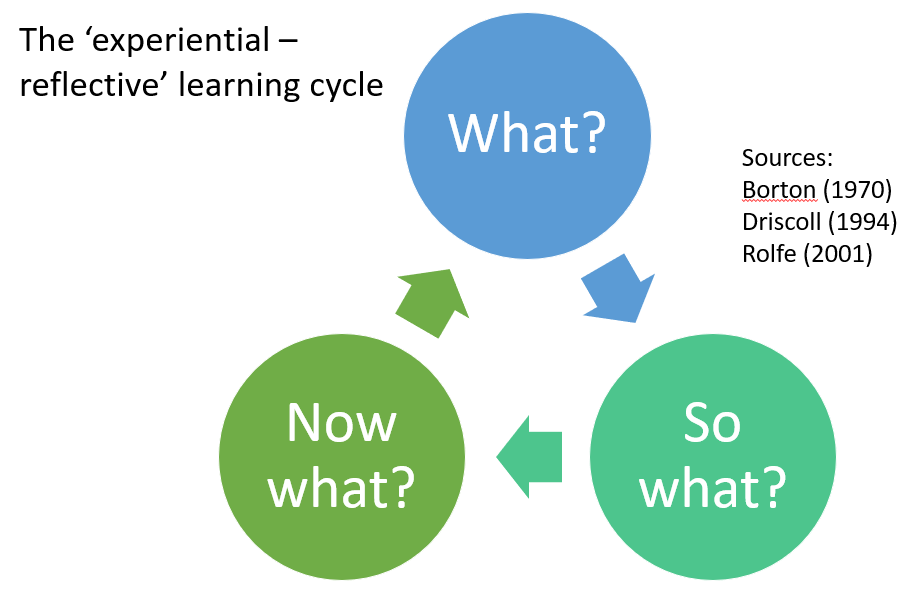

I want to share the idea of a learning cycle…which has the beauty of containing three (seemingly) simple, yet powerful, questions to ask of ourselves/ of the system(s) we play roles within:

The ‘What?’ is about doing something (or observing it being done) and describing what happened. E.g.

- What triggered the event to occur?

- What was trying to be achieved?

- What actions were taken?

- What basis was used for doing these things, in the way(s) they were?

- What was the response, and the consequences?

- …

The ‘So what?’ is about reflecting on the experience6, to derive valuable insights. E.g.

- Why did it turn out that way?

- What could have made it better?

- What broader issues arise from seeing this?

- What is my/our new understanding?

- …

The ‘Now what?’ is about action-oriented reflection7, to consider what might be done based on what’s been learned. E.g.

- What could be done differently?

- Why would this be better?

- What might be the consequences?

- What barriers need to be overcome?

- Who needs to be involved?

- …

If you ponder these questions, you’ll note that they can be explored at a basic reflection and/or a critical reflection level.

The basic level may lead to modest, highly confined, and likely temporary, improvement.

The critical level has the power to transform.

On Transformation

If we want (real) improvement, we must cause ourselves to ‘see the unseen’…but that sounds like a hard thing to achieve.

How might we do this? Well, we probably need to put ourselves in a position to have eye-opening experiences!

“Our [perspective] may be transformed through reflection upon anomalies.

Perspective transformation occurs in response to an externally imposed disorienting dilemma…[which] may be evoked by an eye-opening experience that challenges one’s presuppositions.

Anomalies and dilemmas, of which old ways of knowing cannot make sense, become catalysts or ‘trigger events’ that precipitate critical reflection and transformations.”

“Reflection on one’s own premises can lead to transformative learning.” (Mezirow)

Those eye-opening experiences are sat, waiting for all of us, ‘at the Gemba’ (the place where the action happens).

If you’d like a guide to help you with this then here’s one I prepared earlier.

Where’s the barrier?

Perhaps THE critical part of reflection is to find the actual barriers (constraints) to improvement, to then drill down to their underlying causes and to establish where the power lies to tackle them.

This is important to retain your sanity! There’s little point trying to change something when it’s not in your gift to do so.

- If the power is with you (e.g. in exploring yourself, altering your worldview and/or developing your capabilities), then great. Jump on, strap in, and enjoy the ride!

- If it is elsewhere, then your role (if you so choose to take it) is to work on causing ‘them’ to see what you have seen, via eye-opening experiences, just as you did. Don’t resort to merely writing it down in a report.

A Summary In five bullets:

- ‘Go to the action’ (whatever that is for you) and observe what happens (regularly, respectfully, rigorously)

- Have eye-opening experiences (encounter anomalies to your thinking)

- Pause to reflect (wrestle with those disorienting dilemmas)

- The learning cycle may assist

- Ask yourself, and those with you, what’s beneath this? (what premise(s) do you need to re-examine?8)

- Locate the power to change the premise (ref. dichotomy of control) and act accordingly:

- If it’s with YOU – work with yourself (and with those that can help you)

- If it’s not, work on igniting the fire in relevant others (don’t just ‘tell them’)

-

- …it’s likely to be a combination of the two!

A couple of extra thoughts…

A truth criterion as your anchor

Critical reflection sounds awesome…but against what?

I’m reminded of Peter Checkland around the need for an ‘advanced declaration of what constitutes knowledge of a situation.’

It’s all very well having oodles of reflections, but we could do with an anchor from which to tether them to…such as a desirable purpose.

Otherwise, we might find ourselves indulging in copious amounts of navel-gazing9 and going nowhere.

…and, of course, critical reflection would also include regular reflection on what you’ve defined as your purpose anchor.

Making critical reflection a habit

It’s worth pondering the well-known quote:

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” (Will Durant, writing about Aristotle’s work)

This seems to contradict the ‘thoughtfulness staircase’ picture above…but perhaps it’s elegantly linking the top step back around to the bottom step, in an endless loop.

If we want to become comfortable with, and competent in, critical reflection, we perhaps need to purposefully work on exercises and routines that cause us to experience it repeatedly…thus making it a habit.

I won’t presume to tell you what your routines should be. That’s for you to reflect on…

Footnotes:

1. Thanks Ange 🙂

2. On the topic of reflection: As ever, I am straying into a large field of knowledge, so what I write will be biased to what I have read/ understood (vs. what I have not) and constrained by how deeply (i.e. shallow) I dive within a short blog post.

Reflection could be written about in many different ways e.g. about oneself or about the world around us (and the systems within). A big part of reflection should necessarily be about becoming aware of our own social conditioning and (current) ‘lens’ on the world (including the biases within).

3. Mezirow’s paper (sourced from here) is titled ‘Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: How critical reflection triggers transformative learning’

4. A staircase: I’ve chosen to visualise these four definitions on a staircase (Mezirow did not). I’m not criticising ‘habit’…it’s rather good for when I’m driving my car etc. However, it is the bottom step of the stairs if I want to improve.

5. Time & Space: Many organisations appear not to value time spent (or is that wasted?!) on ‘reflection’. It’s seen as ‘people not doing work’…and yet there’s often a ‘poster on the wall’ championing a learning culture.

6. The ‘So what?’ reflection: This can be difficult to do well because it’s very easy to self-justify and get defensive (and not realise this). This is where Argyris and Schon’s work on productive reasoning fits well.

7. The ‘Now what?’ reflection: Sadly, many people skip getting to the critical ‘so what’ reflections and jump straight into the action piece. However, if we do the ‘so what’ properly, we’ll be working on the ‘right stuff’ in the ‘now what’.

8. Premise to re-examine: This may be the very nature of the system you presume you are working with (ref. ordered vs. complex vs….)

9. Navel-gazing: I’m using this term here to mean ‘becoming excessively absorbed in self-analysis, to the detriment of actually moving forwards.’ However, on checking the definition of navel-gazing online, I love the fact that I find the practice of Omphaloskepsis (navel-gazing in Greek) to be an aid to meditation 🙂 .

There’s a lovely idea which I’ve known about for some time but which I haven’t yet written about.

There’s a lovely idea which I’ve known about for some time but which I haven’t yet written about.

To seek: search for, attempt to find something.

To seek: search for, attempt to find something.